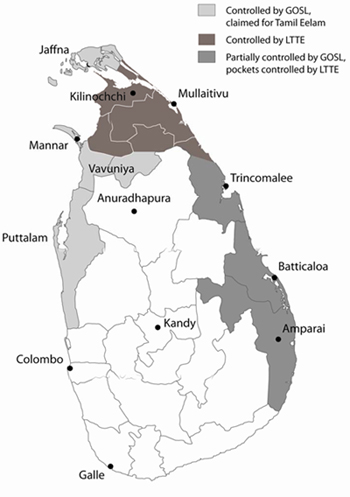

The quote from the South African Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu points to the discursive contestation over nationalist struggles – where a militant movement may be alternatively described as ‘freedom fighters’ or ‘terrorists’ – but also to the political transformation of such movements during transitions to peace and democracy. | Figure 1 Approximate extent of territorial control in Sri Lanka as of January 2006 - "Sri Lanka’s third Eelam War created a political-territorial division of the island with a resultant dual state structure in the North-East. In the context of the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement and based on earlier institutional experiments, the LTTE is currently engaged in a comprehensive process of state building within the areas they control."

|

Although Tutu’s statement refers specifically to the transformation of the African National Congress during South Africa’s transition to liberal democracy, his observations resonate with the politics of naming and transforming the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka. Thus, Nadarajah and Sriskandarajah (2005) show that the language of terrorism has been used to deny LTTE international legitimacy and thereby undermine their political project of Tamil self-determination. Much less has been written about the on-going political transformations within the LTTE. This is surprising and unfortunate, especially since the LTTE is involved in a state building project which may also yield a transformation of the movement itself. The overall purpose of the present article is to address this knowledge gap in regard to the emerging state in North-East Sri Lanka. Based on interviews with the leadership of key LTTE institutions,2 the following sections examine the process of state formation in LTTE-controlled areas, with an emphasis on the functions that are being served and the forms of governance that are embedded in the new state institutions.

The LTTE state structure

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam have for more than two decades sought to deliver self-government for the Tamil nation and homeland (Tamil Eelam) through armed struggle interspersed with ceasefires and peace negotiations ( Balasingham 2004, Swamy 2003). Since 2002, in the context of the 5th peace process,3 there has been a partial shift from military to political means, with a prominent position for the LTTE Political Wing and a comprehensive state apparatus emerging in LTTE-controlled areas. Through a series of military victories in the late 1990s, LTTE had brought extensive areas under its control and created a certain military parity of status with the Government of Sri Lanka (Balasingham 2004, Uyangoda and Perera 2003). Thus, the third Eelam War (1995-2001)4 ended in a military deadlock which together with economic crisis, regime change and favourable international conditions led to a Ceasefire Agreement on 22 February 2002 and subsequent peace negotiations in 2002- 2003.

LTTE is currently in full control of large areas, especially in northern Sri Lanka (Figure 1). Travelling from government- to LTTE-controlled areas resembles a border crossing between two nation-states with well-guarded border control posts where travellers are required to show identity cards, goods are inspected and customs fees are collected. Within the areas they control, LTTE runs a de facto state administration, which includes revenue collection, police and judiciary as well as public services and economic development initiatives. This political-territorial division means that Sri Lanka has a de facto dual state structure with LTTE also exercising considerable influence on state institutions and officials in the government-controlled parts of the North-East province (Shanmugaratnam and Stokke 2005).5 The emerging LTTE state builds on institutional experiments in the period from 1990 to 1995, when LTTE controlled Jaffna and parts of Vanni and established various local administrative bodies. While the control over Jaffna has been lost, these institutions and experiences have been incorporated into the new state building project which is now centred on Kilinochchi. At the same time, local government institutions and officials continue to function within LTTE-controlled areas, which mean that there is a dual state structure also within the areas that are held by the LTTE. Against this background, the present paper examines the nature of LTTE’s state structure in North-East Sri Lanka. The focus is on the character and functions of the state apparatus and the form of governance that is being institutionalised.

In general terms it will be argued that the LTTE state has a primary focus on guaranteeing external and internal security in the context of protracted warfare, but also that there are key state institutions that are geared towards the welfare of the civilian population and the economic development of Tamil Eelam. These state institutions are clearly shaped by the movement from which they have emerged.

On the one hand, the LTTE state institutions contain authoritarian and technocratic tendencies that provide a certain administrative efficiency but prevent democratic accountability. On the other hand, they are also rooted in and committed to the rights, welfare and development of the Tamil community on whose behalf the militant and political struggles have been waged.

While the operation of the new state institutions is circumscribed by the unresolved conflict, this combination of autonomy and embeddedness give the emerging state a substantial degree of administrative capacity. This may provide an institutional basis for a more democratic relationship between the LTTE and citizens in North-East Sri Lanka, but this is contingent on the resolution of the current security situation as well as a willingness within the LTTE to accept political pluralism, human rights and democracy.

Conflict resolution and political transformations

Contemporary academic debates about transitions from violent conflicts to peace revolve around notions of ‘conflict resolution’ (peacemaking) and ‘conflict transformation’ (peacebuilding), where conflict resolution refers to the purposeful elimination of conflict through negotiations and peace agreements (Miall, Ramsbotham and Woodhouse 2005, Wallensteen 2002). Scholars within the conflict transformation approach acknowledge the centrality of formal peace processes but argue that the conflict resolution school focuses too narrowly on elite negotiations and peace pacts, calling instead for attention to the broad and long-term transformation of grievances, forces and strategies (Uyangoda 2005). This implies that the process of building a lasting peace is much wider than the formal negotiations between the protagonists to the conflict. Nevertheless, conflict resolution and conflict transformation are closely linked processes since: “Resolution of a conflict requires a fundamental transformation of the structure as well as the dynamics of the conflict. Similarly, action towards resolution constitutes transformative politics and praxis” (Uyangoda 2005:14).

This means that a peace agreement may provide a necessary but not sufficient condition for sustainable peace. The challenge is to substantiate, in theory and practice, the mutual constitution of conflict resolution and conflict transformation.

While it is increasingly acknowledged that transitions to peace should be conceptualised in a broad manner, there is a danger that the notions of conflict transformation and peace building may end up being too vague and all-inclusive to guide analysis or policy towards peace. Realising this problem, some scholars have sought to disaggregate the process of conflict transformation in order to devise policy tools for peace building. Smith (2004), for instance, argues that peace building can be disaggregated along four main dimensions: (1) to provide security;

(2) to establish the socio-economic foundations of long-term peace;

(3) to establish the political framework of long-term peace, and;

(4) to generate reconciliation and justice.

This has, more concretely, formed a basis for a strategic framework for peace building that has been adopted by the Government of Norway (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2004). Here, a special emphasis is placed on the first three dimensions in Smith’s scheme, broadly corresponding to what is conventionally seen as the three core functions of any modern state: security, welfare and representation. To build peace then translates into systematically addressing functional state failures in regard to security, welfare and representation.

Schwarz (2005) observes that the three core state functions are closely interconnected, sometimes reinforcing and at other times hindering the fulfilment of each other. Thus, security constitutes a precondition for welfare and political participation as much as welfare reduces conflicts and political representation allows for non-violent resolution of conflicts.

Likewise, welfare increases the capacity and propensity for political participation, while representation promotes economic development and social justice. In the case of the emerging LTTE state there is clearly an overarching emphasis on the question of security, but this has gradually been supplemented with an additional focus on welfare and economic development. A highly contentious question in this situation regards the degree and ways in which the emerging state apparatus can serve as a platform for democratic political representation. This requires critical attention to the relationship between institutional change and changing political practices.

Luckham, Goetz and Kaldor (2003) examine this link between formal political arrangements and practical politics in conflict-torn societies, and observe that institutional arrangements affect the range of possible political practices, albeit not in a straightforward manner. For instance, the establishment of democratic institutions does not automatically yield political transformations towards democratic politics. In fact, many of the ‘third wave’ democratic transitions have yielded a co-existence of formal liberal democratic institutions and non-democratic politics (Bratton and van de Walle 1997, Harriss, Stokke and Törnquist 2004, Collier and Levitsky 1997).

This coexistence of democratic institutions and non-democratic politics can be briefly illustrated with reference to Sri Lanka, a formal liberal democracy with successive regime changes through electoral turnovers since Independence in 1948, but also a political system that lies at the heart of the current conflict. In general terms, the contemporary Sri Lankan political system can be described as a majoritarian formal democracy within a unitary and centralised state, with extensive concentration of power and few de facto constitutional and institutional checks on the powers of the executive government (Bastian 1994, Coomaraswamy 2003, Thiruchelvam 2000).

The stakes in the field of politics, in terms of political power, economic resources and social status, are exceedingly high while political parties are fragmented by class, caste, faction, family, ethnicity, region etc. Given these characteristics it is hardly surprising that the Sri Lankan polity has been marked by an intense intra-elite rivalry, yielding instrumental constitutional reforms, populist politicisation of ethnicity, strategic coalitions and crossovers as well as political corruption and patronage. Indeed it seems clear that the dynamics of this political field, despite its formally democratic institutions, have been a decisive factor in the making and continuation of conflicts in post-colonial Sri Lanka (Shanmugaratnam and Stokke 2005, Stokke 1997, Stokke1998).

While institutional arrangements may not determine political practices, Luckham, Goetz and Kaldor (2003) also point out that institutional reforms open up the political space for democratic politics while also being shaped by political struggles over the content of policies and the design of institutions. This means that it is important to pay attention to how different actors partake in the design and reform of political institutions, especially in transitions to democracy and peace (Bratton and van de Walle 1997). This can again be illustrated by the Sri Lankan case and especially the Government strategies for achieving peace through limited institutional reforms within the parameters of the unitary state.

Set against the background of political fragmentation and intra-elite rivalry, successive Sri Lankan government coalitions have sought to depoliticise Tamil nationalism and bring Tamil areas and organisations into ‘normal’ politics within the unitary state rather than offer substantive forms of power-sharing. The People’s Alliance government under the leadership of President Chandrika Bandaranaiake Kumaratunga (1994-2001) sought for instance to depoliticize Tamil separatist nationalism through limited devolution of power to the provinces without granting any special status or guarantee to the North- East.

For the United National Front (UNF) government led by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe (2001-2004) the same depoliticizing effect was sought through social and economic development in the North-East combined with a promise of an open ended process of peace negotiations. Both strategies have met with initial accommodation followed by firm resistance from the LTTE, as they have concluded that these initiatives fail to accommodate their fundamental demand for recognition of Tamil nationhood, homeland and self-determination, but rather shift the balance of power in favour of the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) and the unitary state

For the LTTE this strategy of modest institutional reforms within the parameters of the unitary constitution poses a real danger of leaving them with little or no formal state power. It is in this context that the state building activities of the LTTE must be understood, as a political strategy of institutionalising a ground level reality of dual state power as a precursor to future power-sharing arrangements with either internal or external self government for North-East Sri Lanka. The question then regards the functions and forms of governance that are embedded in these institutions, and the extent to which they may lead to a political transformation of the LTTE towards democratic politics.

The security function: hegemony armoured by coercion

This threefold categorisation of state functions can now be employed to provide a more systematic account of the emerging state institutions in LTTE-controlled areas in North- East Sri Lanka. In general terms, it can be observed that functional state failure, i.e. the inability of the state to fulfil its security, welfare and representation functions, is at the core of the conflict and also the attempt to build a new state apparatus in the North- East. The state building project of the LTTE is also closely linked to their political project of representing the Tamil nation and delivering self-determination for the Tamil nation. On the one hand, it is contingent on the discursive framing of LTTE as the sole representative and guardian of Tamil nationalism. On the other hand, LTTE’s hegemony in Tamil politics is closely related to their military capacity to confront the GOSL and thereby provide a degree of external security, but also their repressive capacity in regard to internal anti-LTTE political and militant forces.

Thus, the possible state power of LTTE is contingent on their ability to inscribe themselves in a Tamil national-popular will and their ability to apply force to maintain external and internal security, i.e. the emerging LTTE state formation rests on “hegemony protected by the armour of coercion” (Gramsci 1971, p. 263). While these militant and ideological dimensions of LTTE are well documented and need no further elaboration here, much less information is available on the building of hegemony through the judicial and police state apparatus.

Present law and order institutions in LTTE-controlled areas date back to the early 1990s when LTTE controlled Jaffna and parts of Vanni. The political background for the creation of the Tamil Eelam judicial system was the experienced failure of the Sri Lankan Constitution to provide a functioning framework for realisation of minority rights and aspirations, combined with the subversion of Rule of Law by the Prevention of Terrorism Act and protracted warfare. This created a need for a functioning judicial system, both to maintain law and order and to reinstate legitimacy for Rule of Law itself: “Therefore we as a liberation movement had to come up with an expeditious solution to prevent the collapse of the social order in the North-East while creating structures that would reflect the Sovereign Will of our people” (E. Pararajasingham, Head of the LTTE Judicial Division) 6

Tamil Eelam Judiciary

|

In the 1980s, before the establishment of a separate judicial system, the LTTE set up village mediation boards, comprised of retired civil servants, school teachers and other local intellectuals. However, these turned out to be highly problematic and created much tension in society, not the least due to the lack of a legal code as basis for adjudication and lack of training and legal competence. Therefore, as LTTE attained increased organisational capacity and territorial control, the village mediation boards were dismantled and a Tamil Eelam Judiciary, a Legal Code and a College of Law were established.

The Tamil Eelam Penal Code and the Tamil Eelam civil code were enacted in 1994. These were based on preexisting laws that were updated and extended to cater for the social issues that LTTE has chosen to focus on, such as women’s rights and the caste systems (TamilNet 25.09.97) 7

We made special laws for women regarding their property rights, rape, abortion etc. Under our laws women are totally free and on par with men in property transactions. As you know, this is not the case under Jaffna’s traditional law, Thesawalamai. Our civil code has done away with the stipulation in Thesawalamai that a woman should obtain her husband’s consent to sell her property. We made caste discrimination a crime. These could be considered some of the milestones of the Thamil Eelam judicial system. (E. Pararajasingham, Head of the LTTE Judicial Division)8

The present Tamil Eelam judicial system includes District Courts that handle civil and criminal cases as well as two high courts, in Kilinochchi and Mullaitivu, with jurisdiction to try certain criminal cases such as treason, murder, rape and arson. There is also a Court of Appeal in Kilinochchi and an apex Supreme Court with appellate jurisdiction over the whole Tamil Eelam.9 Penalties are strict, generally varying from fines to jail terms, but also including rare cases of capital punishment for rape and certain kinds of murder. While critics of the judicial system have questioned the autonomy of the courts in regard to LTTE, others point to the legitimacy of the courts among the civilian population in the North-East (N. Malathy, personal communication).

The Courts are known to be effective so that people who have a choice often take their claims to the Tamil Eelam courts rather than the Sri Lankan courts. The court system is one of the main points of contact the LTTE has with the Tamil public, and it is careful to be seen as just. Despite their relative youth, the judges seem to be perceived by the public as professional. Thus, the present Judicial System carries substantially more legitimacy than the previous citizens’ committees.

The other key institution for maintaining law and order is the Tamil Eelam Police, which was formed in 1991 in the context of a general breakdown of law and order after a decade of warfare. The police force was organised by its current Head (B. Nadesan), a retired officer from the Sri Lankan police, acting upon a direct request from the Leader of LTTE, V. Pirapaharan. Co-ordinated from its headquarter in Kilinochchi, the Police has established local police stations throughout LTTE-controlled areas, with assigned duties of preventing and detecting crime, regulating traffic and disseminating information about crime prevention to the civilian population (B. Nadesan, personal communication). The Head of the Police force emphasise the importance of public relations, both to give the force legitimacy among the Tamil population and as a strategy to prevent crime: The other key institution for maintaining law and order is the Tamil Eelam Police, which was formed in 1991 in the context of a general breakdown of law and order after a decade of warfare. The police force was organised by its current Head (B. Nadesan), a retired officer from the Sri Lankan police, acting upon a direct request from the Leader of LTTE, V. Pirapaharan. Co-ordinated from its headquarter in Kilinochchi, the Police has established local police stations throughout LTTE-controlled areas, with assigned duties of preventing and detecting crime, regulating traffic and disseminating information about crime prevention to the civilian population (B. Nadesan, personal communication). The Head of the Police force emphasise the importance of public relations, both to give the force legitimacy among the Tamil population and as a strategy to prevent crime: "We recruit personnel to Thamileelam Police from the general public and give classes before deploying them in active duty. Many recruits are victims of oppression under the Sri Lankan armed forces. Dedications shown by our police officers in rendering service to our community also contributed to the success of our police service." ( B. Nadesan, Head of Tamil Eelam Police)10

LTTE representatives highlight this community embeddedness of the police as a key factor behind the low crime rates in the North-East. Critics of LTTE, however, argue that the Police force is an integral part of the LTTE armed forces, implying that the low crime rate is due to authoritarian control rather than community policing. In either case, it can be observed that the police and judiciary maintain a high degree of rule of law in LTTE-controlled areas.

This is a point that is generally acknowledged by both LTTE supporters and opponents, allowing the Leader of the Political Wing, to observe that: "Foreigners who visit the Vanni assume that two decades of war would have torn apart the fabric of our society. They expect a total break down of law and order; that crime and corruption would be rife as in societies ravaged by war in other parts of the world. They tell us they are surprised that, instead, they see a society where the Rule of Law prevails, where high social, moral and cultural values are still earnestly upheld." (S. P. Thamilchelvan, Leader of the LTTE Political Wing) 11

In general terms, it can be observed that the judicial and police state apparatus in North- East Sri Lanka strengthens the coercive capacity of the state in the realm of internal security. However, the manner in which these institutions operate, seem to give them a substantial degree of legitimacy among the Tamil civilian population, thus also contributing to LTTE hegemony in the North-East.

The welfare function: Partnerships for relief and reconstruction

Social welfare is the other state function that has been given a central place in the building of the LTTE state, although in a subordinate role to that of maintaining external and internal security through military, police and judicial means. There is a range of institutions serving this welfare function, of which two types deserve special attention. First, there are ‘non-governmental’ organisations that provide humanitarian assistance and social development for war- and tsunami-affected areas and people. The most prominent example here is the Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation (TRO), an NGO with close affiliation to LTTE that relies on international resource mobilisation and partnerships. Second, there are the LTTE departments in the health and education sector, which provide certain basic services to the civilian population but also function as a check on public services provided by the Sri Lankan state.

The Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation (TRO) was formed in 1985 primarily as a self help organisation for Tamil refugees in South India. Since then it has grown to become the major local NGO working in North-East Sri Lanka. Its overall aim is to provide short-term relief and long-term rehabilitation to war affected people in the North-East. TRO has a head office in Kilinochchi, branch offices throughout the North-East, and national organisations in a number of foreign countries with a sizeable Tamil diaspora (e.g. Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, USA). The background for the establishment of TRO has been the devastating human and social impacts of protracted war. With large numbers of internally displaced people and massive destruction of lives and livelihoods, large groups depend on relief and rehabilitation measures by Non-Government Organisations (NGOs). At the same time, the conflict has produced a large and relatively resourceful Tamil diaspora in many countries, especially in Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand (Fuglerud 1999). TRO’s mode of operation has typically been to mobilise resources within this diaspora for a wide range of welfare-oriented programmes in North-East Sri Lanka. Following after the 2004 tsunami disaster, TRO has also been working in partnership with donor countries and international NGOs to channel aid to tsunami affected areas and people.12

TRO’s relief, rehabilitation and development work include a wide range of programmes in education, health, resettlement and housing, food and nutrition, water and sanitation, women and children’s welfare, community rehabilitation, social mobilisation and capacity building, micro credit and vocational training. TRO’s activities in tsunami- affected areas have generally gone from providing immediate relief during the first 3 months, to a recovery phase of up to 1 year where the focus has been on re-establishing livelihoods and income generation (assistance to build and repair boats and engines, providing micro credit for farmers, fishermen and small- and medium-scale enterprises). The current rehabilitation phase (up to 3 years) is focused on permanent housing, public health, vocational training and miscellaneous support for women and socially marginalised groups. While progress in this third phase has been relatively slow for various reasons, including the failure to establish a joint mechanism between the LTTE and GOSL for distribution and administration of foreign emergency aid, TRO representatives can claim that they have a demonstrated ability to work effectively within the prevailing social and political conditions, and to plan and implement relief and rehabilitation programs for war- and tsunami-affected areas in North-East Sri Lanka (L. Christie, K. P. Regi, personal communication).

The main controversy surrounding TRO has been about their autonomy in regard to the LTTE, and especially their possible role in collecting and transferring funds from the Tamil diaspora to the LTTE. Following the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement, TRO has been allowed to register as a non-governmental organization in Sri Lanka and the organisation received an award from President Chandrika Kumaratunga Bandaranaike for its relief work after the 2004 tsunami disaster. But TRO has also become the subject of scrutiny by governments, especially in Canada, Australia, UK and USA, who are concerned that funds may be transferred through front organisations into LTTE, which is included in their list of proscribed foreign terrorist organisations. Countering these accusations, TRO officials have argued that although they work with the LTTE on the ground, their operations and funding efforts are separate from LTTE (TamilNet 29.11.2005).13 While the relationship between TRO and LTTE is contested and controversial, the case of TRO shows how humanitarian relief and rehabilitation within the emerging state relies on partnership arrangements and resource mobilisation in the Tamil diaspora.

What is more surprising is the co-existence and links between local Sri Lankan state institutions and LTTE institutions in key social sectors such as health and education. Throughout the conflict, government services have been provided by the local offices of Government Agents and ministries such as in agriculture, fishery, health and education. LTTE’s militant struggle, while targeting the armed forces and political leaders, has not attacked the local civil administration. This is presented as a conscious strategy, emanating from the realisation that the Tamil civilian population was in need of state services and would be ill served by a total onslaught on the state apparatus (S. Puleedevan, personal communication). This is in contrast to for instance the South African anti-apartheid strategy of disrupting local administration and making communities and cities ungovernable. Likewise, it is in sharp contrast to the onslaught on the Sri Lankan state by the Janathi Vimukthi Peramuna in the late 1980s. Rather, LTTE has sought to make local state institutions work to their advantage and simultaneously developing complementing welfare programmes.

In reality, the civil administration in the North-East is to a large extent under the control of the LTTE. Shanmugaratnam and Stokke (2005, p. 23) observe that “it is common to hear government officials in the NE say that they worked for ‘two masters’, their formal superior and the LTTE, which is often the ‘real boss’.” This situation, which is enabled by the fact that many Tamil government servants identify themselves with Tamil nationalism, has evolved gradually.

One observer describes the situation in areas controlled by LTTE in the early 1980s in the following way: "At the district level, the LTTE staff coordinate their activities with the Government Agent (GA) and his staff. No decisions that concern the welfare of the people or the land is taken by the GA’s office or government officers or committees without consultation with LTTE officers responsible for the sector and/or area. In effect the GA’s office, except for the routine government affairs such as salaries, pensions and other such matters, is used as an arm of the LTTE government." (Neeran 1996, p. 2)14

In this situation of dual powers, health and education remain the responsibility of the Sri Lankan state and teachers are salaried by the Sri Lankan government, but the North- East is generally seen as under-serviced in both health and education. This state failure is experienced as a dramatic relative deprivation when compared to the earlier state and status of education and healthcare in Tamil society. As much as the functioning of the public sector was a key grievance behind the emergence and radicalisation of Tamil nationalism (Stokke and Ryntveit 2000), the current lack of government services are seen as a reminder of the biased distribution of state resources in Sri Lanka (TamilNet 22.09.2002).15

In this situation, the LTTE Department of Education asserts influence on both local state institutions and the relevant Ministries, through direct engagement with local officials or by using the leverage of international non-governmental organisations. For instance, the overall shortage of qualified Tamil teachers has led to an advocacy campaign by the LTTE Department of Education demanding that the Ministry of Education should confer permanency to the large number of temporary teachers in the North-East. Similar advocacy activities in the health sector has focused on the persistent lack of medicines in the North-East as well as the employment status of local health volunteers. Indeed, it can be argued that such advocacy campaigns may actually make Sri Lankan state institutions more accountable and efficient in the North-East than in the rest of the island (S. Puleedevan, General Secretary of the LTTE Peace Secretariat, personal communication). In addition, LTTE also provides own services, especially in the form of primary health care and pre-school education, thus creating an element of division of labour between service provision by the Sri Lankan state and by LTTE state institutions (Sangam.org 02.04.2005).16

Interestingly, the welfare oriented LTTE institutions are characterised by active engagement with external actors, but these are seen as playing a supportive role in regard to the emerging state apparatus. Such external actors include, first and foremost, the Tamil diaspora, but also foreign donors and even Sri Lankan state institutions. This is in stark contrast to the aforementioned law-and-order institutions, where there are few examples of regular links with foreign governments, international NGOs and the Tamil diaspora, and certainly not with the GOSL. Such arrangements are enabled by the conception of humanitarian assistance and welfare delivery as a matter of technocratic development administration, which is clearly related to but nevertheless seen as relatively de-linked from the conflict itself.

Economic development: State coordination, enterprise development and taxation

In general terms it can be observed that the LTTE state formation has had a main focus on the security function of the state, in the context of protracted warfare. Social welfare is an important additional focus, but this has been subordinated to the security needs of the LTTE and the emerging state. After the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement, when the pressing security concerns were temporarily resolved and replaced with hopes for a political solution to the conflict, a political space was opened up for a new focus on economic development, not the least as development became a point of convergence between the LTTE, the GOSL and the international actors involved in the peace process (Shanmugaratnam and Stokke 2005, Sriskandarajah 2003).

The LTTE and the GOSL reached an agreement in the early stage of the process to jointly address humanitarian needs in the war-torn areas and use this as a precursor to substantive discussions on the core issues of power sharing and constitutional reforms. This created optimism in regard to the prospects of relief and rehabilitation, but also for the possibilities of moving beyond immediate humanitarian needs towards more long-term development. In reality, this strategy of using development as a trust-building first step towards conflict resolution failed to meet the high expectations, mainly due to divisive politicisation of the question of development administration for the North-East (Shanmugaratnam and Stokke 2005).

A Secretariat for Immediate Humanitarian and Rehabilitation Needs in the North and East (SIHRN) was established at the second round of negotiations (October-November 2002),17 but was soon crippled due to the unresolved legal status in regard to receiving and disbursing development funds. Later, the peace process stalled in 2003 over the question of interim development administration in the North-East, while a final agreement to create a joint Post-Tsunami Operational Management Structure (P-TOMS) was put on hold by the Sri Lankan Supreme Court in July 2005. This means that whereas development provided a meeting point for the protagonists, the question of development authority inevitably led to the political question of power sharing arrangements.

While the LTTE has seen it as a non-negotiable necessity to establish an interim development administration with substantive power and a guaranteed position for the LTTE (LTTE 2003), Sinhalese opposition forces has expressed the fear that such an interim administration would institutionalise a form of power sharing that would undermine the sovereignty and integrity of the unitary state. Given the fragmented Sinhalese polity and the centralised nature of the Sri Lankan constitution, the opposition managed to hamper the attempts to create an interim development administration as well as the subsequent efforts to create a joint mechanism for handling aid after the 2004 tsunami (S. Puleedevan, personal communication).

Still the peace process had important implications for development in the North-East, by removing government restrictions on travels and flows of goods and by bringing international development funding, organisations and programmes to the North-East. This has posed new opportunities and challenges for the LTTE in the realm of development policy and planning.

The development-to-peace design of the fifth peace process also raised the question about what kind of development model the LTTE would follow. Shanmugaratnam and Stokke (2005) observe that there was no dialogue between the LTTE and the GOSL on development policy, creating speculations among intellectuals about whether the LTTE would subscribe to the neo-liberal development policy of the GOSL and their international sponsors:

In informal discussions, some opined that being ‘statist’ in nature the LTTE would not opt for an economic policy based on free markets and privatisation. They argued that the Tigers’ nationalist ideology and need to consolidate a popular base in the NE were not compatible with the politics and economics of neo-liberal globalisation. ... Some pointed to past statements by Pirapaharan on economic policy, particularly to the leader’s emphasis on ‘self-reliance’ and ‘economic equality’, and believed that there would be open disagreements between the government and the LTTE on the neo-liberal economic policy for reconstruction and development of the NE. (Shanmugaratnam and Stokke (2005, p. 10)

Such a critique of neo-liberal development was not raised by the LTTE during the talks. On the contrary, the LTTE chief negotiator and political strategist A. Balasingham stated that the LTTE was “in favour of an open market economy based on liberal democratic values” (TamilNet 25.04.2003).18 Balasingham made, however, a key distinction between “the urgent and immediate problems faced by the Tamil people” and “the long-term economic development of the Tamil areas” (TamilNet 25.04.2003).19 This distinction had the effect of making short-term development interventions a technocratic and centralised exercise of assessing and accommodating the local needs for relief and rehabilitation (ADB, UN and WB 2003), while postponing the question of development policy.

The development work of the LTTE after the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement has focused on the development of institutional capacity to address relief and rehabilitation needs and, not the least, the need for coordination of development initiatives (S. Ranjan, M. S. Ireneuss, personal communication). Addressing a meeting of UN and international NGO delegates, S. P. Tamilchelvan, emphasised “the importance of co-ordinating and synchronizing the activities of humanitarian agencies” (LTTE Peace Secretariat 15.06.2004).20 To meet this need for coordination, the LTTE established a Planning and Development Secretariat (PDS) in 2004 (TamilNet 01.01.2004)21, and declared that it would be “the pivotal unit that will identify the needs of the people and formulate plans to carry out quick implementation with the assistance of experts from the Tamil Diaspora” (S. P. Tamilchelvan, LTTE Peace Secretariat 15.06.2004).22

Planning and Development Secretariat (PDS) is now responsible for integrating plans and need assessments from various organizations in order to increase the effectiveness of resettlement, reconstruction and rehabilitation. This role became especially clear after the 2004 tsunami, when PDS and the LTTE tsunami task force sought to coordinate the many international NGOs involved in relief and rehabilitation, through forums for information exchange and by assigning responsibilities in terms of functions and localities (Planning and Development Secretariat 2005).

The approach to development that seems to dominate the PDS is one that emphasises the fulfilment of basic needs and the need for centralised planning and coordination. When it comes to the actual delivery of development, however, the LTTE state relies on partnership arrangements with international aid agencies and NGOs combined with mobilisation of resources, skills and persons in the local and international Tamil community. Tamil NGOs such as TRO and the Economic Consultancy House (TECH) play an important role in this regard.

TECH was established in 1992 as a non-profit non-governmental organisation. Its specified objectives are to formulate and implement “economically viable, technically feasible and socially acceptable projects to enhance the quality of life of the people” (LTTE Peace Secretariat 01.05.2004).23 TECH is funded primarily by local and expatriate Tamils and has international branches in countries with a strong Tamil diaspora (including Canada, UK, Australia, Japan and Norway).

In their work they collaborate with local and international NGOs, international agencies (e.g. ILO and UNICEF), local government agents and the PDS. TECH’s mode of operation resembles that of TRO, but has a stronger focus on economic development through utilisation of human skills and technology. Thus, TECH is supporting ‘technology-based community development’ and seeking to enable business development without creating dependencies (M. Sundarmoorthy, personal communication).

Towards this end they operate a range of projects in agriculture, fishery, alternative energy, industrial development and environmental protection. For instance, in the energy sector, TECH is working to develop and introduce alternative energy based on solar panels and wind mills. They also run an agricultural development programme, which includes an Integrated Model Farm outside Kilinochchi. The farm provides training to farmers, seed for paddy, small grains, seedlings for fruit, trees and vegetables, fertilizers, and improved breeds of cattle and poultry. Research is done on the prevention of animal and plant diseases, on wind and solar energy and on new forms of irrigation. TECH is also operating a Rural Development Bank, offering saving accounts and loans for agricultural, self-employment and business development initiatives.

TECH represents a technology-oriented development model with guided enterprise development in close affiliation with the LTTE. To the extent that TECH is indicative of LTTE’s approach to development, it implies that they have not adopted an explicit neo-liberal development policy but have rather strengthened their capacity for development planning and coordination and for project implementation through partnership arrangements with NGOs and funding agencies, i.e. a model of state-led enterprise development. However, this model seems to contain a basic contradiction between entrepreneurship and authoritarian regulation, which is especially visible in the controversies around LTTE taxation and its possibly stifling impact on entrepreneurship and enterprise development in the North-East.

The LTTE tax regime has developed gradually and unevenly, but includes a range of direct and indirect taxes in both the area that they control and in territories held by the GOSL. Taxes that were collected clandestinely before the Ceasefire Agreement are now collected more openly and systematically. For instance, Tamil public servants are commonly asked to contribute a certain percentage of their monthly salary as income tax, manufacturers and service providers are taxed a percentage of their monthly income and farmers and fisherfolk are asked to contribute a share of their output either in cash or in kind (Sarvananthan 2003). There are also indirect taxes in the form of customs fees on goods being brought into LTTE-controlled territory, in the form of vehicle registration tax in LTTE-controlled areas and as tax on property transactions in Jaffna. Although relatively little is known about the exact nature of the LTTE tax system, it can be identified as a challenge for both democracy and economic development in the North-East. In terms of democracy, the problem lies in the weak horizontal accountability relationship between citizens and the LTTE state and the overall illegitimacy of a ‘war tax’ in the current context of ‘no war/no peace’ (Nesiah 2004). Regarding development, the question is about the impacts of taxation on the viability of enterprises. Sarvananthan (2003, p. 12) argues that the extraction of capital through taxation is “stifling entrepreneurship in particular and economic revival in general”, thereby being “one of the major impediments to economic revival in the N&E province.” Vorbohle (2003) supports this view that LTTE taxation is bringing down the profits of Jaffna entrepreneurs, but also draws attention to the impact of political uncertainty, lack of transparency and predictability on the business rationale of local entrepreneurs, generally making them invest very cautiously:

The highly arbitrary and therefore unpredictable character of the actual and expected protection money did not allow the local entrepreneurs to estimate their potential profit and implicated the risk of being left with marginal profit. Therefore, the consequence expressed by most of the entrepreneurs was not to improve and expand their enterprises considerably for the time being. It was especially the expectation, that the higher the profit of an entrepreneur was, the higher would the demanded amount of protection money be (and this in a disproportionate way) that made them reluctant to expand and substantially invest in their enterprises. (Vorbohle 2003, p. 30)

Vorbohle also finds that the Jaffna entrepreneurs experience their position in regard to the LTTE as weak in the sense that they have limited leverage in regard to the extent and manner of taxation or the use of collected taxes for enterprise development. This indicates a problem of representation and embeddedness for the LTTE state, hampering the emergence of productive synergies between private entrepreneurship and a developmental state.

Political representation: Towards democratic governance?

Having examined the main institutions and functions of the LTTE state, it is time to return to the question of what kind of governance that is embedded in these institutions and about the prospects for democratic representation emanating from this institutional basis. Political representation is clearly the most controversial and contested function of within the emerging LTTE state. It follows from the review of LTTE state institutions that the dominant form of governance in LTTE-controlled areas is that of a strong and centralised state with few formal institutions for democratic representation. It should be noted, however, that this hierarchical form of governance is complemented with elements of partnership arrangements, especially in regard to social welfare and economic development. This indicates that the LTTE state holds a potential for transformation towards governance based on state coordination and facilitation of non state actors in the market and in civil society.

In discussing the making of governance, Pierre and Peters (2000) point out that governance can be seen as a product of structures and institutions or as an outcome of dynamic and relational political processes. Whereas the former perspective supports the view that “if you want to get governance ‘right’ you need to manipulate the structures within which it is presumed to be generated”, the latter position sees governance as “a dynamic outcome of social and political actors and therefore if changes are demanded then it is those dynamics that should be addressed” (Pierre and Peters 2000, p. 22, emphasis in original). These perspectives are complementary rather than mutually excluding, as democracy and governance are constructed at the interface between structural-institutional conditions and political practices (Luckham, Goetz and Kaldor 2003).

In agreement with this view of governance dynamics, the hierarchical governance arrangement of the LTTE state can be seen as a product of the post-colonial political experiences with majoritarian politics, protracted war and unfulfilled political pacts, combined with LTTE’s character and practices as a disciplined militant organisation engaged in armed struggle.

This may lead to the conclusion that successful conflict resolution, providing substantial security and power sharing arrangements, is both a precondition and a source of political transformations. This argument is often heard in pro-LTTE political circles, where it is argued that the LTTE will be both willing and capable of transforming itself and the state apparatus towards a more enabling and democratic form of governance if the structural problem of insecurity is resolved (G. G. Ponnambalam, personal communication).

Opponents of LTTE, however, argue that the Tamil Tigers’ political record shows that substantial devolution of power to the North- East under LTTE control is more likely to produce authoritarianism than democracy. In support of this mode of reasoning, references are made to various non-democratic practices, for instance that LTTE has not participated in electoral politics or organised local elections in the areas they control, but have instead displayed intolerance towards competing Tamil forces and have a record of human rights violations that includes use of child soldiers.

While these are valid criticisms, it is problematic to rule out the possibility of future political transformations. Without taking a definite position on the future political trajectory of the LTTE, it seems pertinent to bring out three recent political changes in the North-East that may indicate that LTTE’s stands on political pluralism, human rights and centralisation are not given once and for all. First, regarding democratic participation, it can be observed that the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement has yielded a conditional shift in LTTE’s struggle for self-determination from militant to political means, with the Political Wing emerging in a coordinating role in regard to both the peace process and the local state building. There has been no attempt to build a political party, but the LTTE openly supported the Tamil National Alliance during the 2004 parliamentary elections and has held regular consultations with TNA MPs since then.

While there were numerous accusations of election fraud, the strong support for TNA is taken as a mandate from the Tamil electorate for the LTTE. Thus LTTE claims to hold a popular-national mandate and be concerned with political representation, even though they have not constituted themselves as a political party and participated directly in democratic elections, implying that this may change if there is a secure basis for self-government. In this context, it may be significant that TNA has announced that it will participate in the 2006 local elections in the Trincomalee and Mannar Districts (TamilNet 12.02.200624 and 15.02.2006 25).

Second, regarding human rights, it is noticeable that LTTE has created a North-East Secretariat on Human Rights (NESOHR), not the least to counter the dominant discourse on LTTE’s human rights record. This ‘human rights commission’ has no formal recognition or representation in international human rights forums, but nevertheless functions as an intermediary between international human rights organisations and the LTTE. NESOHR’s prime function lies in advocacy on behalf of the rights of Tamils, directed mainly towards non-local actors. However, the secretariat also performs an advocacy role locally as a human rights commission for the Tamil population, maintaining records of rights violations and sometimes mediating disputes (N. Malathy, personal communication).

The secretariat has, for instance, communicated complaints from parents about child recruitment, occasionally resulting in the release of underage recruits from the LTTE. This indicates that the secretariat may at times perform the role of an oversight institution within the LTTE state. Clearly, the autonomy of the secretariat in regard to the LTTE should not be exaggerated, but taken together with the judicial system it could be seen as a nascent institutional basis for horizontal accountability which could be furthered in a post-conflict political context.

Third, regarding centralisation, there are emerging experiments with decentralisation and community participation in the planning and implementation of reconstruction and development in tsunami-affected areas (S. Ranjan, personal communication). Under the leadership of the PDS, local reconstruction and development after the 2004 tsunami disaster have been carried out with participation from community based organisations and their representatives in Village Development Forums. These Forums have to a certain extent become arenas for local deliberation, including some critical expressions in regard to LTTE practices. These experiences may in the future be transferred from the tsunami-affected coastline and be utilised in the reconstruction and development of war-affected areas. If successful, it may also provide a basis for revitalisation of local elected councils (Pradeshiya Sabha), which are now generally non-operational (M. S. Ireneuss, personal communication).

As much as governance and democracy is conditioned by complex structural institutional context as well as the diverse powers and strategies of multiple political actors, it is obviously futile to try to predict the political trajectory of the LTTE and the emerging state formation in regard to political representation. The LTTE has a demonstrated ability to govern the areas they hold, but doing so largely by authoritarian rather than democratic means. It remains a challenge for LTTE to utilise their present institutional basis for political transformations towards democratic governance. Such political transformations will certainly be contingent on the external security situation, the extent to which LTTE is willing and capable of creating political spaces for democratic representation, and the manner in which pro-democratic forces in Tamil society will fight for and utilise such spaces. Resolving the security problem in tandem with political transformations towards democratic governance remain prime challenges of peace building in North-East Sri Lanka.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s third Eelam War created a political-territorial division of the island with a resultant dual state structure in the North-East. In the context of the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement and based on earlier institutional experiments, the LTTE is currently engaged in a comprehensive process of state building within the areas they control.

Within this emerging state apparatus there has been a strong focus on external and internal security issues, with an additional emphasis on social welfare and economic development. The dominant form of governance embedded in the LTTE state institutions is that of a strong and centralised state with few formal institutions for democratic representation, but there are also elements of partnership arrangements and institutional experiments that may serve as a basis for more democratic forms of representation and governance. This is contingent, however, on both a peaceful resolution of the current state of insecurity for Tamils and the LTTE, and on the facilitation and dynamics of pro-democracy forces within the LTTE and in Tamil society at large.

Acknowledgements

This research project has been supported by the Norwegian Research Council. The fieldwork in Kilinochchi was facilitated by LTTE Peace Secretariat. I am deeply grateful to the Peace Secretariat and especially to the Secretary General S. Puleedevan for their invaluable assistance. Mr. Yarlavan at the Peace Secretariat was relentless in his efforts to arrange interviews and facilitate my fieldwork in every possible way. In Oslo, Yogarajah Balasingham has been very helpful in arranging meetings with visiting delegations from North-East Sri Lanka. I am also grateful to the participants in a Nordic Workshop on “War and Peace in Sri Lanka” (Uppsala University, 26-27 January 2006) for valuable comments on an earlier draft. Needless to say, the interpretations and arguments contained in this article remain my sole responsibility.

References

ADB, UN and WB (2003). Assessment of Needs in the Conflict Affected Areas of the North East (Draft). Colombo: Asian Development Bank, United Nations, World Bank.

Balasingham, A. (2004). War and Peace. Armed Struggle and Peace Efforts of Liberation Tigers. Mitcham, UK: Fairmax.

Bastian, S. (ed.) (1994). Devolution and Development in Sri Lanka. Colombo: International Centre for Ethnic Studies.

Bratton, M. and N. van de Walle (1997). Democratic Experiments in Africa : Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics) Cambridge University Press.

Collier, D. and Levitsky, S. (1997). Democracy with adjectives: Conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Politics 49(3):430-451.

Coomaraswamy, R. (2003). The Politics of Institutional Design. An Overview of the Case of Sri Lanka. In. S. Bastian and R. Luckham (eds.). Can Democracy be Designed? The Politics of Institutional Choice in Conflict-torn Societies. London: Zed.

Fuglerud, Ø. (1999). Life on the Outside. The Tamil Diaspora and Long Distance Nationalism. London: Pluto.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Harriss, J., Stokke, K. and Törnquist, O. (2004). Politicising Democracy: The New Local Politics of Democratisation Houndmills: Palgrave-Macmillan.

JBIC (2003). Conflict and Development: Roles of JBIC. Development Assistance Strategy for Peace Building and Reconstruction in Sri Lanka. Tokyo: Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

LTTE (2003). The proposal by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam on behalf of the Tamil people for an agreement to establish an interim self-governing authority for the Northeast of the island of Sri Lanka. Kilinochchi: LTTE Peace Secretariat.

Luckham, R., Goetz, A. M., and Kaldor, M. (2003). Democratic Institutions and Democratic Politics. In, S. Bastian and R. Luckham (Eds.), Can Democracy be Designed?: The Politics of Institutional Choice in Conflict-Torn Societies. Zed, London.

Miall H., Ramsbotham, O. and Woodhouse, T. (2005). Contemporary Conflict Resolution: The Prevention, Management and Transformations of Deadly Conflict Cambridge: Polity.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2004). Peacebuilding – a Development Perspective. Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Neeran (1996). The Civil Administration in Thamil Eelam. (first published in Tamil Voice).

Nadarajah, S. and Sriskandarajah, D. (2005). Liberation struggle or terrorism? The politics of naming the LTTE. Third World Quarterly 26(1): 87-100.

Nesiah, V. (2004).Taxation without representation, or Talking to the Taxman about Poetry. Lines 2(4).

Pierre, J. and Peters, B. G. (2000). Governance, Politics and the State. Houndmills: Macmillan.

Planning and Development Secretariat (2005): Post Tsunami Reconstruction: Needs Assessment for the NorthEast. Kilinochchi: PDS.

Sarvananthan, M. (2003) What Impede Economic Revival in the North and East Province of Sri Lanka? Lines 1.

Schwarz, R. (2005). Post-Conflict Peacebuilding: The Challenges of Security, Welfare and Representation. Security Dialogue, 36(4): 429-446.

Shanmugaratnam, N. and Stokke, K. (2005). Development as a Precursor to Conflict Resolution: A Critical Review of the Fifth Peace Process in Sri Lanka. Noragric, Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

Smith, D. (2004). Towards a Strategic Framework for Peacebuilding: Getting Their Act Together. Oslo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Evaluation Report 1/2004.

Sriskandarajah, D. (2003). The Returns of Peace in Sri Lanka: The development cart before the conflict resolution horse? Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, 2.

Stokke, K. (1997). Authoritarianism in the age of market liberalism in Sri Lanka. Antipode, 29(4): 437-455.

Stokke, K. (1998). Sinhalese and Tamil nationalism as post-colonial political projects from ‘above’, 1948-1983. Political Geography, 17(1): 83-113.

Stokke, K. and Ryntveit, A. K. (2000). The Struggle for Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka. Growth and Change, 31(2), 285-304.

Swamy, M. R. N. (2003). Tigers of Lanka: From boys to guerillas. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa.

Thiruchelvam, N. (2000). The Politics of Federalism and Diversity in Sri Lanka. in Y. Ghai (ed.). Autonomy and Ethnicity. Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-ethnic States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tutu, D. (2000). Foreword. in A. Sachs. The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter London: Paladin.

Uyangoda, J. (Ed.) (2005). Conflict, Conflict Resolution and Peace Building. University of Colombo: Department of Political Science and Public Policy.

Uyangoda, J. and Perera, M. (2003). Sri Lanka’s Peace Process 2002. Critical Perspectives. Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

Vorbohle, T. (2003). “It’s only a cease-fire”. Local entrepreneurs in the Jaffna peninsula between change and standstill. Student Research Project, Faculty of Sociology, University of Bielefeld.

Wallensteen, P. (2002). Understanding Conflict Resolution: War, Peace and the Global System. London: Sage.

Interviews L. Christie, Planning Director, Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation

C. Ilamparithi Head, Jaffna Branch of the LTTE Political Wing

M. S. Ireneuss Director, Secretariat for Immediate Humanitarian and Rehabilitation Needs in the North and East

Rev. Fr. M. X. Karunaratnam Chairperson, North-East Secretariat of Human Rights

N. Malathy North-East Secretariat of Human Rights

B. Nadesan Head, Tamil Eelam Police

G. G. Ponnambalam Member of Parliament and General Secretary, All Ceylon Tamil Congress

S. Puleedevan Secretary General, LTTE Peace Secretariat

S. Ranjan Acting Secretary General, Planning and Development Secretariat

K. P. Regi Executive Director, Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation

M. Sundarmoorthy Director, The Economic Consultancy House

T. Yarlamuthan Director, Special Task Force, Vadamarachchi East

1 Department of Sociology and Human Geography, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1096 Blindern, 0317 Oslo, Norway. E-mail:

2 Qualitative interviews were conducted in Kilinochchi (August 2005) with the leadership of the LTTE Peace Secretariat, the LTTE Planning and Development Secretariat (PDS), the Secretariat for Immediate Humanitarian and Rehabilitation Needs in the North and East (SIHRN), the Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation (TRO), the North-East Secretariat on Human Rights (NESOHR), the Tamil Eelam Police, the LTTE Special Task Force for Tsunami-affected areas, and The Economic Consultancy House (TECH). Meetings and interviews have also been held in Oslo (2003-2005) with representatives from LTTE’s Political Wing (Jaffna Branch), the Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation, the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, the Secretariat for Immediate Humanitarian and Rehabilitation Needs in the North and East (SIHRN), the Tamils Rehabilitation Organisation (TRO) and the North-East Secretariat on Human Rights (NESOHR). 3 The present peace process follows after four failed attempts at conflict resolution through negotiated settlements: the Thimpu talks in 1985, the Indo-Lanka Accord in 1987, the Premadasa/LTTE talks in 1989-90 and the Bandaranaike/LTTE talks in 1994-95 (Balasingham 2004, JBIC 2003, Uyangoda 2005).

4 The first Eelam war broke out after the anti-Tamil riots of July 1983 and ended with the Indo-Lanka Peace Accord in July 1987. The second Eelam war started after the departure of the Indian Peace- Keeping Force in 1989 and the failed peace talks with the government of President Premadasa in 1989-90 and lasted until the peace negotiations with the Government of President Kumaratunga in 1994-1995. The third Eelam war ensued shortly after the breakdown of the peace negotiations in April 1995 and lasted until the informal ceasefire agreement of December 2001. This ceasefire was later formalised through a Memorandum of Understanding on 21 February 2001 and a formal Ceasefire Agreement on 22 February 2002. At the time of writing (January 2006), there has been a gradual escalation of violence and a growing sense that the Ceasefire Agreement is likely to collapse and be replaced by a fourth Eelam war.

5 To acknowledge the existence of a dual state structure and to examine LTTE as a political actor that is involved in a state building process is highly controversial in Sri Lanka. The World Bank’s country representative to Sri Lanka, Peter Harrold,came under heavy criticism in March 2005 for recognising the existence of an unofficial LTTE state. In an interview with Sunday Times, Harrold stated that: “Given the fact that there is an officially recognized LTTE-controlled area, a kind of unofficial state, and since it is a party to the ceasefire agreement with the Government, the LTTE has the status of a legitimate stakeholder” (Sunday Times 3 March 2005). The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), a Marxist Sinhalese nationalist party which was part of the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) government at the time, demanded that the statement should be withdrawn or the Bank should remove Harrold from his position as he had “overstepped his duties” and made a statement that “undermines sovereignty of Sri Lanka and challenges the authority of the state” (TamilNet 07.03.2005, http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=14405).

6 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=79&artid=10277 7 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=7328

8 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=79&artid=10277 9

10 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=12927 11 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=11045

12 www.troonline.org 13 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=16434 14 http://www.sangam.org/ANALYSIS_ARCHIVES/civil.htm 15 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=7519 16 http://www.sangam.org/articles/view2/?uid=957 17 Government of Sri Lanka Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP),

18 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=8853 19 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=8853 20 http://www.ltteps.org/?view=213&folder=2 21 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=73&artid=10836 22 http://www.ltteps.org/?view=213&folder=2 23 http://www.ltteps.org/?view=198&folder=2 24 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=17174 25 http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=17202

|