News on New Delhi's foreign policy has recently been among the top stories in the media. On April 11, 2005, India started a strategic partnership with China, and, on June 29, 2005, signed a 10-year defense agreement with the United States. Western observers, however, have paid less attention to an ambitious Indian move in the military field: Project Seabird.

Birds Eye View of Project Seabird

This plan -- with origins from the mid-1980s -- is to be assessed in light of two geopolitical triangles juxtaposing on the Indian Ocean's background: U.S.-India-China relations and China-Pakistan-India relations. In this complicated geopolitical configuration, New Delhi is not simply a partner of China or the United States: India is emerging as a major power that follows its own grand strategy in order to enhance its power and interests.

India's New Diplomacy

India is emerging as a decisive player in U.S.- China bilateral relations, often regarded as the real landmark of this decade's geopolitics. New Delhi launched a potentially revolutionary "strategic partnership for peace and prosperity" with China on April 11, 2005. The move was aimed at ending the Sino-Indian border dispute on Aksai-Chin (existing since 1962), and at boosting mutual trade and economic ties. Prospects for a more cooperative relationship between the two Asian giants are to be read in light of regional powers' ambition to reshape world order along the guidelines of a balanced multipolarity -- a goal already expressed by China, France and Russia, among other states.

However, in order to rise as a great power, India needs more than economic assets and a strong military; "infusions of U.S. technology and investments in infrastructure," as former Indian envoy Lalit Mansingh told the press on July 14, are necessary for India to "become a major global player." These Indian needs -- along with concerns over the Indian Ocean's security -- form the context that led New Delhi on June 29 to sign a 10-year defense agreement with Washington. Strategic partnerships are not intended to challenge the U.S. directly, but rather to obtain economic, technological and military power rapidly. Thus, India's strategy is not contradictory. On the contrary, it is a sophisticated policy whose endeavor is to create the necessary balance of power in its geostrategic environment in order to concentrate on economic, technological and military matters indispensable to its emergence as a true great power. [See: "Great and Medium Powers in the Age of Unipolarity"]

Interestingly, as the Wall Street Journal reports, U.S. President George W. Bush clearly said that the United States is involved in helping India "become a world power" -- which could be a sign of Washington's gradual acceptance of an embryonic multipolarity in Asia. However, U.S. fundamental interests in developing better relations with India are the necessary containment of China, and New Delhi's help in the war against militant Islamic groups -- a need that is growing stronger due to the unstable political landscape in Pakistan. [See: "India: A Rising Power"]

Project Seabird

Such a political and diplomatic framework is the background of India's ambitious Project Seabird, which consists of the Karwar naval base, an air force station, a naval armament depot, and missile silos all to be realized in the next five years.

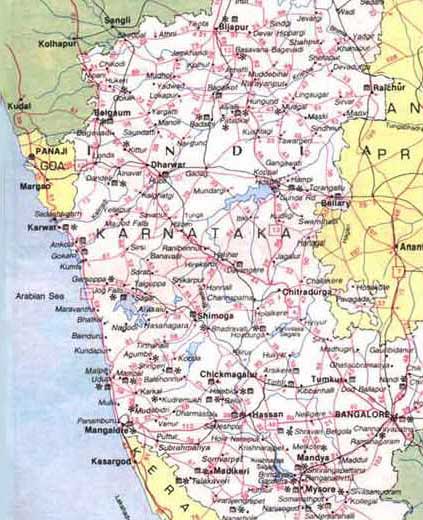

Indian Defense Minister Pranab Mukherjee said on May 31 that the naval base INS Kadamba in Karwar, Karnataka state will protect the country's Arabian Sea maritime routes. Kadamba will become India's third operational naval base, after Mumbai and Visakhapatnam. Six frontline Indian naval ships, including frigates and destroyers, took part in the commissioning. Kadamba extends over 11,200 acres of land, along a 26-km stretch of sea front, and it will be the first base exclusively controlled by India's navy. Eleven ships can be berthed at Kadamba once the first phase of it is achieved; 22 ships after the second phase of construction will be completed around 2007, according to INS Kadamba's first Commanding Officer Commodore K.P. Ramachandran as reported in the international media. Moreover, the new harbor is designed to berth ultimately 42 ships and submarines once completed.

The geopolitics of the Arabian Sea and the Western Indian Ocean largely explain India's determination in such an $8.13 billion enterprise. The China-Pakistan-India triangle is more than ever the Arabian Sea's decisive geostrategic setting. For the Chinese, this trilateral relationship is crucial for two reasons: from the point of view of energy security, the Arabian Sea and Pakistan are Beijing's access points to the oil-rich Middle East; from the perspective of military security, Pakistan provides China an effective counter-balancing partner in front of India's ambitions.

Therefore, faced with geographic constraints, the Chinese successfully proposed to Islamabad back in 2001 the sharing of the Gwadar naval base. This latter serves the Chinese purposes in three ways: first, it serves as a tool to secure Beijing's access to the Gulf's resources; second, it is a useful military base to counter Washington's influence in Central and South Asia: in fact, the Sino-Pakistani agreement came into being just four months after U.S. troops entered Kabul in 2001; third, Gwadar functions as an excellent wedge between India and the Middle East and as an offset against India's naval power.

Sino-Pakistani cooperation has contributed to accelerating India's plans to regain the upper hand in the Western Indian Ocean.

India and U.S.-China Competition

The slowly escalating competition between the U.S. and China has helped to create a fertile environment for India's ambition to gain status as a great regional power. Cooperation with China has become one of the most discussed issues in India's business community for a number of reasons, but the loudest talk has been the opportunities based in combining India's "software" economy with China's "hardware" economy. There are also geopolitical motivations for India to align itself with China. Both countries favor multipolarity: for Beijing, this trend will help to weaken U.S. influence in its sphere of influence; for New Delhi, this shift creates an environment for it to gain influence over its near-abroad.

However, there are drawbacks for India to aligning too closely with either power. Washington has often touted the "natural alliance" between the two expansive, multi-ethnic democracies, but it is on military issues that India would most like to develop its relationship with the U.S. During the recent tsunami relief effort, the two states' navies worked together, which helped to cement their budding military-to-military ties. The U.S. would like for India's navy to serve as a bulwark against China as Beijing becomes more active in the Indian Ocean. Also, there are some areas where the U.S. Navy cannot operate, such as the Malacca Straits, where India's presence might be seen as less threatening than that of the U.S.

However, there are drawbacks to aligning too closely with either power for India. On energy security, India and China have found cooperation to be easy in Iran, but, as finding new sources of oil becomes more difficult, there are bound to be areas of friction. For example, China views the Andaman Sea off Myanmar's coast as an important source of oil to fuel the economic expansion of China's western provinces. However, New Delhi sees building a port at Dawei, Myanmar as a major component to its future security strategy for the region. China's presence in the area is an unwelcome development for India.

Washington's relationship with two of India's neighbors, Iran and Pakistan, is the major sticking point in their relationship. The U.S. prefers to starve out the current government in Iran, but India sees the country as an important source of energy for its expanding economy. Washington's support of Pakistan's military since September 11, 2001, has been protested loudly and repeatedly by India. However, the U.S. is unlikely to abandon this support because the Central Asian countries aligned with China in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (S.C.O.) have recently signaled that they favor a U.S. withdrawal from the region. Because of this, the U.S. will now need Pakistan's support even more for the success of its operations in Afghanistan.

Even though Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and President Bush announced on July 18 a new agreement for the U.S. to cooperate with India's civilian nuclear industry in return for international oversight and a continued moratorium on nuclear weapons testing, Washington's support for New Delhi's nuclear industry will continue to be tempered by India's unwillingness to sign the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

In this environment, India has been very successful in using strategic partnerships with both Washington and Beijing to further its interests on the Indian Peninsula and Indian Ocean. For the near term, New Delhi can be expected to emphasize points of agreement with China and the U.S., while looking to gain better positioning for itself in the region.

Another Interested Player: Russia

India's increasing ambitions in the Western Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf will most likely draw in actors other than the U.S., China and Pakistan. The Russian Federation will no doubt assume greater importance for India as a major source of military hardware that is currently fueling India's drive for a blue water navy. Since the flagship of Karwar, INS Kadamba is a Russian-built aircraft carrier with Russian-designed Mig-29 aircraft, India will rely on Moscow for a major portion of spare parts and maintenance in the short and medium run.

India's growing naval ambitions represent an expanding area of interest for Russian manufacturers. Currently, China is a major customer for Russian-made submarines, surface ships and surface-to-surface weapons systems that are adding to Beijing's growing naval strength. Since Karwar, INS Kadamba is expected to accommodate an increasing number of military ships, India may augment its indigenous production capacity with ever-growing numbers of Russian-made vessels.

This may spark a naval race in the Western Indian Ocean if China places its most advanced vessels in Pakistan's Gwadar Port. The two countries have much to gain from cooperation in the business and trade sphere, and an outright military clash between their navies is unlikely. However, the two could be drawn into a confrontation if the vessels of other navies, aligned to either state, get involved in a conflict.

If more political and military problems develop between India and Pakistan, then even a growing rapprochement with China may not prevent a dangerous escalation for New Delhi. Washington may find itself powerless to act in this case, as it will be unwilling to compromise both its tactical relationship with Islamabad and its growing "alliance of need" with New Delhi. On the other hand, Russia may well benefit from such a scenario, as it has experience in supplying two belligerents fighting each other at the same time. Moscow sold weapons to both Iraq and Iran in the 1980s when the two countries were at war. Presently, Russia will be content in selling naval ships and technology to both India and China, even as the two states may be inching towards competition in the strategically important Western Indian Ocean.

There is much to gain from cooperation for India and China when it comes to shipments of oil from the Persian Gulf. A major disruption of such flow -- whether from an intentional military escalation by the two states or even from a combination of factors having less to do with both countries, such as an Iranian military action or a terrorist attack -- will have negative consequences for the economies of both countries. Peaceful shipments of oil and gas are in everyone's interests. Still, the construction and use of both Karwar and Gwadar will certainly invite some form of competition, as India and China may view each other's minor advancements in naval technology, number of vessels or any other technical factor as a less-than-benign show of strength.

The dynamics of the region still call for a balance of power approach rather than a straight alliance. China-Pakistan cooperation will figure prominently for Indian decision-makers, just as India's warming relationship with Washington may be a concern for China's People Liberation Army planners. The construction of both Karwar and Gwadar may signal both India's and China's readiness to upgrade their naval strength from brown water to blue water capability, but cordial relations between both states may be no guarantee of the peaceful use of the Western Indian Ocean.

Relying more and more on advanced military technology that is not currently indigenously produced by both states, India may turn to Russia to supplement its increasing naval needs. This may enhance Moscow's status in the region, as well as offer the possibility of countering Washington's current undisputed naval primacy in that part of the world.

Conclusion

The rise of India as a major power, coupled with the better-known -- and frequently analyzed -- Chinese rise, is changing the structure of the world system. Not only is U.S. "unipolar" hegemony in the Indian Ocean facing a challenge, but the strategic triad U.S.-Western Europe-Japan, which has ruled the international political economy for the past few decades, is now also under question. Nonetheless, when confronting the new reality, Washington seems eager to help India rise in order to counter Beijing's growing influence. Moreover, India's increasing power is also a part in the process of a major shift occurring in international relations, from U.S.-based unipolarity to a "multifaceted multipolarity," which could be the prelude of a new multipolar order. [See: "The Coming World Realignment"]

In this transition phase, the Indian Ocean's security will be a crucial issue. Massive military build-ups have already started, and the risks of miscalculations by the traditional and new great powers are getting higher. We can expect the South Asian region to be one of the system's key areas to be watched in the next decade.

Report Drafted By:

Adam Wolfe, Yevgeny Bendersky, Dr. Federico Bordonaro

|