The Indian Ocean Region

Sri Lanka’s Strategic Importance

P.K. Balachandran

Special Correspondent for Hindustan Times in Sri Lanka 30 May 2005

If the world is showing an extraordinary interest in the peace process in Sri Lanka; if the western donor nations have given $3 billion for post-tsunami reconstruction work in the island; and if India wants to be kept informed about what is going on constantly, it is because of Sri Lanka’s strategic importance. If the world is showing an extraordinary interest in the peace process in Sri Lanka; if the western donor nations have given $3 billion for post-tsunami reconstruction work in the island; and if India wants to be kept informed about what is going on constantly, it is because of Sri Lanka’s strategic importance.

This conclusion is inescapable if one reads ‘Strategic Significance of Sri Lanka’ by Sri Lankan researcher Ramesh Somasundaram of Deakin University.

In this 2005 publication, brought out by Stamford Lake, Somasundaram tells us that Sri Lanka has had strategic importance in world history since the 17th century, attracting the Portuguese, Dutch, French, the British, and the Indians, in succession. Now, we may add a new entity, “the international community”, to the list of interested parties.

The author gives three reasons for such interest:

(1) Sri Lanka is strategically situated

(2) It is ideally situated to be a major communication center, and

(3) It has Trincomalee, described by the British Admiral Horatio Nelson as “the finest harbour in the world”.

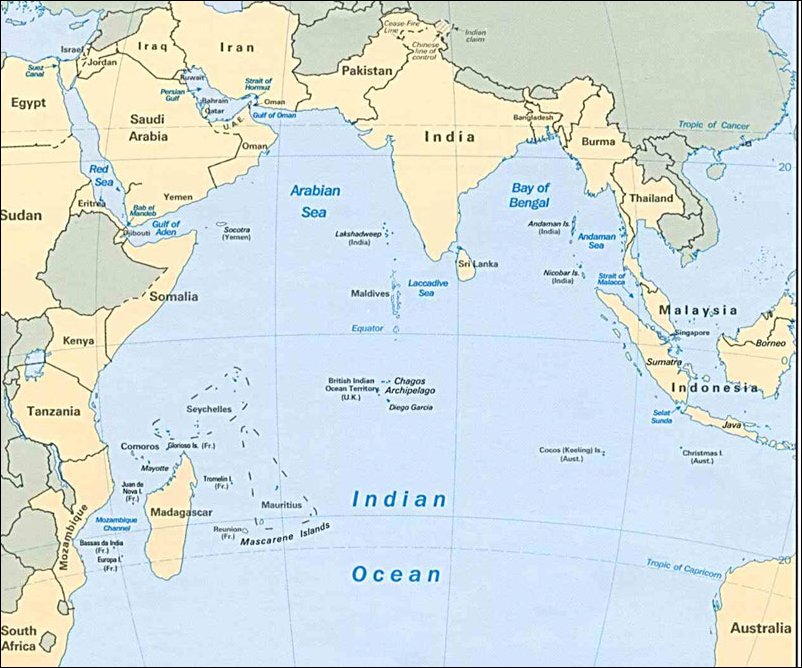

Sri Lanka occupies a strategic point in the Indian Ocean, whose vast expanse covering 2,850,000 sq miles, touches the shores of the Indian subcontinent in the North; Malaysia, Indonesia and Australia in the East; Antartica in the South; and East Africa in the West.

The Indian Ocean encompasses the Red Sea approach to the Suez Canal, and the approaches to the oil-rich Gulf, the Cape of Good Hope and the Strait of Malacca, which is a major sea route between the West and the Far East.

Sri Lanka, with its natural harbour of Trincomalee, is at a strategic point in the whole region, having global significance in the modern age, Somasundaram notes. The Trincomalee harbour, he adds, is placed in a strategic point near the Bay of Bengal and is one of Sri Lanka’s “most valuable assets”.

The entrance to the harbour is four miles wide and five miles across, East to West. The inner harbour (which lies in the North) covers about 12 sq miles and is securely enclosed by outcrops of huge rocks and small islets. A remarkable feature is the great depth of the inner harbour, he says.

During the period of sailing ships, the harbour could ensure the safety of a whole fleet during the monsoon, from October to March. A fleet, so protected, was in a position to dominate the Bay of Bengal and the Eastern Sea.

“Thus any power that controlled this harbour had a great advantage from a naval and strategic perspective,” Somasundaram observes. He goes on to say that the fact that the British had Trincomalee enabled them to control their Empire in India, effectively. During World War II, Trincomalee protected the British Seventh Fleet. It proved invaluable after the British lost the Singapore naval base to the Japanese in 1942.

Ideal for nuclear submarines

Trincomalee has immense significance in this age of nuclear weaponry and nuclear submarine-based missile systems also, the author points out.

“Given the depth of the harbour, nuclear submarines are able to dive low within the inner harbour to effectively avoid radar and sonar detection,” he observes.

Somasundaram shows how diplomatic relations between the indigenous Kandyan kingdom and the European powers in the 18th and 19th centuries; the post-war/post-independence diplomatic relations of the Ceylon government; and the relations between Sri Lanka and India since the 1980s, have all revolved round who will use Trincolmalee harbour and how it should be used.

Portuguese were first see value of Trincomalee

It was the Portuguese Admiral, Alfonso Albuquerque, who first saw the value of Trincomalee and made it part of his grand design of having bases in far flung areas to control the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean and protect Portugal’s maritime and imperial interests.

Albuquerque set up bases in Malacca in the Malay Peninsula, controlling the access to the South China Sea and the Far East; in Goa in the West coast of India; Socotra in the Arabian Sea; Colombo, and then Trincomalee, in Sri Lanka.

Subsequently, successive Western powers, the Dutch, the French and the British, emulated the Portuguese way of dominating the Indian Ocean. The Dutch took over Trincomalee in the 17th century, beating the French to it though the latter had the sanction of the Kandyan king to possess Trincomalee. Subsequently, the British spent much time and energy getting it from the Dutch.

In the 18th century, when the King of Kandy wanted to get rid of the oppressive Dutch, he sent word to the British in Madras seeking help and offering Trincomalee harbour as bait. Though the British wanted Trincomalee and sent an emissary, John Pybus, to the Kandyan court, they were reluctant to take on the Dutch because they were at peace with the Dutch in Europe at that time. This reticence led to bad relations between the Kandyan King and the British.

But by 1780, Britain itself was at war with Holland and also with the French, and this time, every effort was made to seize Trincomalee from the Dutch, whether the King of Kandy liked it or not.

When the British did seize Trincomalee, it became Britain’s first territorial possession in Sri Lanka. And interestingly, Trincomalee was also the last place in the island they gave up. It was much after they gave independence to Sri Lanka!

The significance of the take over of Trincomalee was realized by the highest in Britain at that time. In a letter to Lord Cornwallis, the then Governor General of India, Prime Minister William Pitt said that seizing Trincomalee from the Dutch as soon as hostilities had begun in Europe, had prevented the French from taking it and using it as base to attack the British in the Cape of Good Hope.

During the 19th and the earlier part of the 20th century when the British expanded their possession on the Eastern, Western and Northern sides of the Indian Ocean, making it a “British Lake”, Trincomalee played a major role as a base and a coal storing/refueling centre. Its strategic significance only increased with the opening of the Suez Canal because the canal led to an increase in shipping between the West and the East.

During World War II, Trincomalee became the home of the British Eastern Fleet and Prime Minister Winston Churchill strictly ordered that nothing should be done to weaken the naval base there.

When oil replaced coal as fuel, Trincomalee began to be a major base for storing oil. During World War II, the British built 101 giant oil tanks there, each tank being able to hold 15,000 tons of oil.

Ceylon’s Defence Pact with Britain in 1947

When the British Empire was being folded up in stages after World War II and India had been given independence in 1947, Ceylon’s independence was only a matter of time. The British were ready to go from Ceylon, but only if they were able to continue using Trincomalee and other military bases built during the War, which they considered essential for the defense of their possessions in South East Asia and the Far East, and also their trade in the region.

With the full consent and approval of the Ceylon’s first Prime Minister, DS Senanayake, the British entered into a Defence agreement with Ceylon in 1947 which provided for the use of Trincomalee, the airbase at Katunayake, and if necessary, other establishments too. “The Defence agreement was an essential prerequisite to independence,” says Somasundaram. Prime Minister Senanayake entered into the agreement primarily to keep India at bay, though the ostensible reason was that Sri Lanka had no means to defend itself against anybody.

However, within ten years of the signing of the Defence agreement, the British had to leave Trincomalee and Katunayake because the Leftist nationalist government of SWRD Bandaranaike asked them to quit.

But fortunately for Sri Lanka (or Ceylon as it was then called), the British did not make a fuss when asked to go. They had realised, by then, that they were no longer a sea power, worthy enough to maintain bases in far-flung areas. The failure to seize the Suez Canal through war in 1956 had taught them this lesson, Somasundaram points out.

Sri Lanka as an ideal communication centre

In the modern era when communication is key, Sri Lanka’s location has been found to be ideal to locate communication centres. Kandy’s fine climate was not the only reason why Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in the South East Asia, chose it to locate his headquarters. Command was communication, and Sri Lanka was ideally suited for that function.

In 1951 came an agreement with the US to relay Voice of America (VOA) programmes over Radio Ceylon (which was then a popular radio station in the vast Indian subcontinent), in return for getting new and modern broadcasting equipment from the US. According to Somasundaram, the VOA used the facility in Sri Lanka to broadcast to all of Asia, including Central Asia, where the Americans were trying to weaken the hold of the Soviets.

By now, the US had replaced Britain as the dominant power in Asia, and it needed military and communication bases all over the continent.

Enter India By 1954, India was beginning to show an interest in Ceylon, albeit very tentatively. Somasundaram quotes an early Indian strategic thinker, RR Ramachandra Rao, as saying in 1954 itself that India had “very real interest in ensuring that no hostile power should establish itself in Ceylon”.

More pointedly, Ramachandran Rao said: ” Foreign airstrips and naval control of Trincomalee would unbearably expose the Indian peninsula to air and sea bombardment and assault along her extensive coasts. Ceylon is within Indian defence area, at the very heart centre of the Indian Ocean defence.”

India-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987

According to Somasundaram, the India-Sri Lanka Accord of July 1987 and the deployment of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) were “ostensibly” meant to find a solution to the Tamil ethnic/separatist problem within a united Sri Lanka, but their “real” objective was to secure for India strategic control over Sri Lanka.

India feared encirclement by hostile forces. It had problems with all its neighbours, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and China. China was in cahoots with the Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and Nepalese. The US and Pakistan were close allies particularly because of the Pakistani role in Afghanistan, where the US was fighting a proxy war against the Soviets. India, on the other hand, had continued its close ties with the Soviets to the chagrin of the US.

India feared that the JR Jayewardene regime in Sri Lanka, which was lurching towards the West, would soon be a part of a Western alliance against India, because of the latter’s support for the cause of the minority Tamils in the island. The Indian support for Tamil militants after the 1983 riots was propelling Jayewardene towards the US-led camp.

To add to India’s fears, in 1985, Jayewardene reminded British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that the Defence pact the British had signed with Sri Lanka in 1947 was still there, not having been abrogated formally.

India was worried about the influx of foreign intelligence personnel into Sri Lanka (specifically, Israelis fronting for the US); the fate of the Trincomalee harbour; and the use to which the vast VOA facilities was being put. India felt that the US was using the communication facilities at the VOA station in the island to spy on India and communicate with US submarines in the region. And British mercenaries from the Channel islands-based KMS Ltd were training the Sri Lankan armed forces.

This was the reason why India appended to the India-Sri Lanka accord of July 1987, an exchange of letters between President JR Jayewardene and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

Through the letters, the two leaders agreed that: (1) Trincomalee or any other port of Sri Lanka, will not be made available for military use by any country in a manner prejudicial to India’s interests.

(2) The work of restoring and operating the Trincomalee oil tank farm will be undertaken as a joint venture between India and Sri Lanka.

(3) Sri Lanka’s agreement with foreign broadcasting organisations will be reviewed to ensure that any facilities set up are used solely as public broadcasting facilities and not for any military or intelligence purposes.

However, when India and Sri Lanka did sign the accord and the IPKF was deployed, neither the US nor the UK raised a little finger. By then, equations had changed.

“Both Britain and the US viewed the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka as one which was really the concern of India, and that India should therefore play a major role in obtaining a political solution to this,” Somasundaram observes.

In fact, the US had by then assigned to India, the role of its proxy in the region. Indicating a new trend in US thinking on relations with India, Henry Kissinger said in an article he wrote in Newsweek in 1988: “India will play an increasing international role. Its goals are analogous to the British east of Suez in the nineteenth century - a policy essentially shaped by the Viceroy’s Office in New Delhi. It will seek to be the strongest power in the subcontinent, and will attempt to prevent the emergence of a major power in the Indian Ocean and South East Asia."

Whatever the day to day irritations between New Delhi and Washington, India’s geopolitical interest will impel it over the next decade to assume some of the security functions now exercised by the US.”

It is in accordance with this role that India has assumed charge of refurbishing and running the Trincomalee oil tank farm in a joint venture with the Sri Lankan government. It is no secret that India is in Trincomalee for strategic purposes and that the Ranil Wickremesinghe government gave the oil tank farm to India primarily for the defence of Sri Lanka.

India has also seen to it that the Trincomalee harbour is not handed over to any foreign power. Significantly, it was India which did the clearing and mapping of the Trincomalee and Colombo harbours after the tsunami.

|