Queimada - Gillo Pontecorvo's Burn!

- as long as there are empires, there will be wars -

[DVD available at Amazon.com] Review by Joan Mellen

Courtesy: Cinema Magazine - Issue:32, Winter 1972-73 "... The young boy who guards the captured Dolores stays with him and provides Pontecorvo with a means of allowing Jose Dolores to give his ideas expression through dialogue. Jose Dolores does not assail his captor; he tries to inspire and convert him. He tells the young man that he does not wish to be released because this would only indicate that it was convenient for his enemy. What serves his enemies is harmful to him. "Freedom is not something a man can give you," he tells the boy. Dolores is cheered by the soldier's questions because, ironically, in men like the soldier who helps to put him to death, but who is disturbed and perplexed by Dolores, he sees in germination the future revolutionaries of Quemada. To enter the path of consciousness is to follow it to rebellion.....Pontecorvo zooms to Walker as he listens to Dolores' final message which breaks his silence: "Ingles, remember what you said. Civilization belongs to whites. But what civilization? Until when?" The stabbing of Walker on his way to the ship by an angry rebel comes simultaneously with a repetition of the Algerian cry for freedom. It is followed, accompanied by percussion, by a pan of inscrutable, angry black faces on the dock. The frame freezes, fixing their expressions indelibly in our minds.." Comment by tamilnation.org "..But imagine it happens: Killinochchi is flattened, Mr P is dead, LTTE dissolved. Will the Tamil dream of a Tamil Eelam die? Of course not. It will be revived, and new cycles of violence will occur. And probably new CFAs. And possibly the same mistake, confusing ceasefire with peace, using it as a sleeping pillow to do nothing..." Conflict Resolution in Tamil Eelam - Sri Lanka: the Norwegian Initiative- Professor Johan Galtung

Gillo Pontecorvo's Burn! must surely be one of the most underrated films of recent years. This can be explained in part by its involved and intricate plot which, on first viewing, is difficult to follow. Sir William Walker (Marlon Brando) soldier of fortune, adventurer and an envoy of the British Crown is sent during the 1840's to an island named Quemada. The island was originally burned to cinder in the scorched earth conquest by the Portuguese who claimed it as a colony- hence the name "Quemada" which means "burnt." Walker's mission is to foment a revolution against Portugal among the oppressed peasantry with a view to replacing Portuguese control with that of Great Britain. He arms a peasant named Jose Dolores whom he first tests for daring and bitterness. With a small band of followers, Dolores, guided by Walker, robs the Bank of Portugal of its gold and goes on to lead the struggle against the Portuguese. After victory, Dolores discovers that the new ruler of the island will be not himself, but a local bourgeois named Teddy Sanchez.

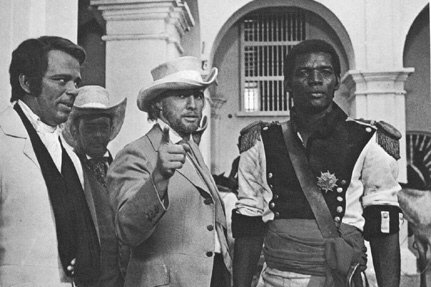

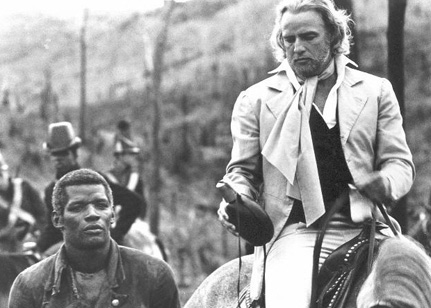

Marlon Brando as Sir William Walker

|

Walker, having provoked peasant revolt to remove Portugal, has organized the settler bourgeoisie, warning them that the peasants will go beyond independence, demanding economic and political control to effect social equality. The settlers are used by Britain to protect British investment and her access to Quemada's resources. "Independence" is translated into replacement of Portugal by a small settler ruling class militarily supported by Britain. For the peasants, one master replaces another. Their misery and powerlessness continue. It is a prefiguring of today's neo-colonial pattern. Dolores is outraged by this cynical denial to him of the fruits of struggle and he assumes the throne of the former Portuguese Viceroy by force. But he discovers that although he possesses momentary power, he lacks the means to feed his people or to sell the sugar. There is no knowledge of world trade or alternative markets. Teachers and technicians do not exist. In short, his people are without the very accoutrements of that civilization which oppressed them in the first place. Unable to see a way out and with sugar rotting and piling up on the docks, Dolores steps down reluctantly, allowing Sanchez to take control. But the settler commander General Prada is quicker than Sanchez in realizing that Quemada can be kept open to foreign investment and bourgeois rule rendered secure only if the rebels are suppressed and permanently disarmed.

Ten years pass. Walker, lacking apparent purpose in life, is now dissolute and living on the margins of English society. Jose Dolores again leads his starving people in a new rebellion aimed directly at the landed settler rulers. This threatens the entire structure of British economic control with implications reaching further than Quemada. Such a revolt, if successful, would spread through the Caribbean and beyond.

The British turn again to Walker, hoping to exploit both his knowledge of the peasant movement and his old relationship with Dolores. He is asked to return to Quemada and put down the rebellion. Walker accepts. He attempts to contact Dolores, thinking to trade upon their old association, but it is this very past which has opened the eyes of Dolores to Walker, whom he spurns. Now openly the professional mercenary, Walker pursues Dolores ruthlessly, burning half the island while uprooting and killing people, animals and vegetation in his path. He develops a theory that the guerrillas can be defeated only if the peasants among whom they take shelter and who supply them are burnt and driven out of all their villages. The vegetation and trees must be denuded since they too hide the rebels. The logic of defeating a popular movement is inexorably genocidal, entailing total devastation. Dolores is finally captured and hanged, refusing Walker's "offer" to escape. Dolores has learned that freedom must be seized in struggle. And he knows the offer to free him is designed to demonstrate his subordination. He also realizes that Walker, having smashed the rebellion, wants to avoid creating a martyr and a legend. Dolores, in cool defiance, prefers death as his fulfilment. Walker is personally undermined by this stark contrast between Dolores' satisfaction in moral conviction and his own emptiness, which he only now fully registers. The taste of victory is bitter.

His business finished, Walker is stabbed to death on the dock by a porter a moment before embarking. Quemada's people are awakened, emboldened, and irreconcilable. The camera pans to many worn faces, their rebellion unchecked and the example of Dolores burned into their consciousness. The political aspirations of Burn! are ambitious. Unlike The Battle of Algiers, Pontecorvo's earlier film, which takes the easier target of colonialism and the desire for independence, without examination of social formations or the political consciousness of the F.L.N., Burn! recognizes that direct colonial rule is but one form of control. Without goals that go beyond mere physical absence of the colonizer's army, economic and social exploitation will be maintained for alien interests by intermediaries, independent in name alone. Neo colonialism is shown a far more invidious and clever enemy. The powerful evocation of the dynamics of America's practice in Vietnam, with its graphic depiction of "Vietnamization," must surely be a major reason for the critical skittishness towards Burns! in this country. Pontecorvo has Walker make his next stop Indochina on first leaving Quemada, a piece of historical impressionism, since France and not England occupied Indochina in the 1840's. It is a bitter irony when his friend Jose Dolores, not yet awakened to betrayal, innocently offers Walker a toast "to Indochina."

United Artists, as Pauline Kael put it, "dumped" the film without advance publicity and screenings. They made Pontecorvo change the occupier from Spain to Portugal, presumably because the Spanish market for all United Artists films was in jeopardy. They made the English title of the film the absurdly imperative "Burn!" rather than the appropriate translation, "Burnt," which states the inexorable fact, thus implying the film's endorsement of the tragedy it depicts. Involved too is the crass sensationalism of invoking "burn, baby, burn" of ghetto insurrections. This, aimed at the black market, inverts the film's meaning, for Portugal and Britain burned Quemada, not the victimized populace, who would never call for the "burning" of their own homes. Burn! may have been buried because United Artists doubted the film would do well, but the distributor willed its unhappy fate. They were disturbed by the incendiary nature of a subject with which they did not care to be closely identified. If Portugal and England were safer destroyers for United Artists, the film's relentless association of racism (the condescending attitude of Walker toward Jose Dolores throughout) with imperialism brought the theme even closer to home. The Battle of Algiers, despite its acclaim, had already suffered a distribution and publicity blackout in the United States, and Burn! goes deeper and farther. Here, far more than in Algiers, Pontecorvo explores Fanon's theme that through long delayed and liberating violence the oppressed are returned to self-respect and adulthood. After attacking their first detachment of Portuguese soldiers, Dolores and his people burst into an orgy of dance and song that lasts far into the celebrating night. After generations of passivity before abuse, they emerge as autonomous people. It is entirely possible that there are circumstances in which a company like United Artists might even be prepared to lose money!

What makes Burn! more interesting than The Battle of Algiers is that it raises those questions which Algiers, in its more pristine detachment, evades. The problem of what happens when a revolutionary organization takes power in an over-exploited country is hinted at in Algiers when Ben M'Hidi advises Ali La Pointe: "It's difficult to start a revolution, more difficult to sustain it, still more difficult to win it," but it is after the revolution that "the real difficulties begin."

Burn! takes on this challenging theme. One of the film's most subtle insights is that colonialism so succeeds in damaging its victims that should they take power, they have in advance been deprived of the means of exercising it. "Who will run your industries, handle your commerce, govern your island, cure the sick, teach in your schools?" Walker asks Jose Dolores, confident of his superior position. "That man or this one?" he continues, pointing contemptuously to the bodyguards of Dolores who stand helplessly before him. "Civilization is not a simple matter. You can't learn its secrets overnight."

Burn! is an intensely romantic movie, a seeming contradiction given the relentlessness of its politics. It opposes "Western Civilization" (an evil because it has been racist and exploitative) to the purity of its victims, who can see nothing of value in a civilization which forever holds them down. But the sugar cane cutters are the true creators of the civilization which they reject as "white." "We," declares Jose Dolores to Walker, "are the ones who cut the cane." The labor which has led to great wealth is subsequently denied its producers. That it could not exist without them slowly dawns upon Dolores as a transforming discovery. From this flows confidence and single mindedness.

Pontecorvo unfortunately makes a facile identification between liberation for Quemada's slave descendants and a rejection of "white civilization." Because the vast wealth exacted by colonial countries from the labor of their victims has given rise to a flourishing culture, it does not follow that the arts, sciences and technology made possible are themselves hateful. The fact that white Europeans are associated with this civilization accounts for the racism of the Europeans, who must denigrate those from whom they plunder, but it does not validate a racism in inverted form. This is what Pontecorvo unwittingly does when he allows Dolores to prophesy not merely the end of an order which depends upon exploitation, but also the culture which it has spawned. Since all culture has similar origins, the sentiment casts the advocate of emancipation in the role of destroyer. But the burden of the film is to present Dolores and his people as the carriers of a different society, one which would end exploitation and create a corresponding culture. It is clear that the accumulation of capital, which permits technical development and a culture requiring leisure, draws upon this labor. The social basis of Western Civilization, certainly in its industrial and technological phase, is traced in Burn! to its brutal source. The last words of Jose Dolores are meant to taunt Walker with his obsolescence: "Civilization belongs to whites. But what civilization? Until when?" The words fall short, although they gain power as the last statement of a man giving his life to his deepest convictions. Because the film raises this idea without exploring it, the source of the projected new civilization remains obscure - as it must - for it is surely destined to take the best of bourgeois culture as a point of departure rather than retreat, if it is to be a culture transcending the subjugation of one class by another. Pontecorvo has said that "the third world must produce its own civilization and one of the weaknesses of the third world today is that its culture is not a new product which has rid itself of white culture, but is a derivation of this culture.'" But an emergent people will take what is useful to them and build from there. In any event, no culture is a new product. Such a view is hardly historical, let alone Marxist.

And, Pontecorvo, after all, in describing the struggle of Jose Dolores, projects not a "new" ideology but that of Marx, who was both European and a product of European capitalism and civilization. "Between one historical period and another," says Sir William, readying himself for battle against Dolores and the rebels, "ten years may be enough to reveal the contradictions of a century."

Pontecorvo applies the words of Marx, as well he might, since a new ideology is not required. Nor does Pontecorvo care that Walker uses Marxist terminology and categories before the Communist Manifesto was written! Why then does he, speaking through his characters, offer in the film a blanket condemnation of all the ideas, values and philosophies to appear in Europe since the Greeks? "If what we have in our country is civilization," says one of the rebels, "we don't want it." Yet in the next breath his ideas are those of Marx and Engels: "If a man works for another, even if he's called a worker, he will remain a slave." These contradictions permeate the film and engender not only a certain feeling of anachronism, but a lack of intellectual clarity, especially disturbing in a film which aims to enlarge our understanding of the nature of neo-colonialism and its relation to culture. There are other undeveloped aspects of the film. In the service of Britain, Sir William Walker is ready to kill Jose Dolores when he threatens British privileges and interests. But Walker feels deep affection for the rebel leader who has played Galatea to his Pygmalion. Indeed his fondness for Dolores is almost as obsessive as his later quest to capture him, and, at the end, Walker is shattered by Dolores' contempt. This is one of the most potentially illuminating and subtle themes in the film. Walker's fascination with the vitality and innocence of Dolores is in counterpoint to his frenzy when he is rejected, even as the colonizers want the love and approval of those they oppress at the same time as they would destroy them for exposing the perpetrators to themselves. This allows psychological verisimilitude to Walker when he returns to Quemada as a ruthless warlord who will burn every blade of grass to prevent Dolores' rebellious ideas from spreading to other colonies and islands where Royal Sugar maintains interests. A major weakness, however, is that this ambiguity of response is evident in Brando's performance, but inadequately developed in the film. The problem is that the face of Brando easily conveys irony and nuance. He is at his best when a situation is ambiguous. But the film seems to deny ambiguity when we are expected to believe that Walker, without self-examination, will renounce all humanity in the service of an absent master- for pay so meagre it is not enough even to be called "gain."

Sir William Walker (Marlon Brando) meets the porter Jose Dolores (Evaristo Marquez) |

Psychological motivation required more careful delineation. As it stands, in the middle of the film Brando, is unable to carry the degeneration of Walker when he has become a brawling drunkard. The action and melodrama, no matter how many fires are set, is too weak to conceal the hiatus between one aspect of the characterization, the external, and the other, the inner life of Walker. The bridge of a psychological relationship between Walker and Dolores, oppressor and oppressed, is not constructed. Pontecorvo is himself too facile in accounting for Walker's transformation: "Walker changed because he discovered that there was nothing behind the side he helped... Men like Walker, full of vitality and action, then change the direction of this vitality. They go to sea, buy a boat, drink, beat people up. They don't believe in anything.'"

This is meant to explain why Walker returns to work for Royal Sugar to rid the island of its rebels, i.e. to a man empty of values one side is not perceptibly different from another. But this reduces Walker to a cardboard figure, and Brando is uncomfortable with the conception, imparting to his Walker that very psychological nuance which the film itself does not consistently fulfill. Hence we miss in Burn!, until the very end, that moment of self-confrontation and discovery in which Walker registers his emptiness and becomes ready to do anything. We have instead his departure to "Indochina" in one sequence and the sight of a slovenly Brando in the next. There is almost a suggestion here that Pontecorvo fears that moments of psychological insight in a film involve indulgence, a resort to what vulgar Marxists might call "bourgeois individualism." More the pity, because the spectacle of personal damage drawn upon and inflicted by imperialism upon its own adherents could only have made more rich the portrait of deterioration in so bold and talented man as Walker. Given the enormous resource Pontecorvo had in Brando, he neglected an important opportunity to create a character at once more powerful and tragic for being able to see more deeply into himself.

As in Algiers, Pontecorvo used primarily non-professional actors in Burn! Besides Brando, the only professional was Rento Salvatori who plays the social democratic leader Teddy Sanchez, an easy tool who is eliminated when he perceived: "if there had not been a Royal Sugar, there might not have been a Jose Dolores." General Prada was played with wit and aplomb by a lawyer, the President of Caritas in Colombia. Mr. Shelton, the representative of Royal Sugar who accompanies Walker during the last half of the film, was performed by the administrator for British Petroleum in Colombia. He played himself-convincingly and with ease. Only in Evaristo Marquez (Jose Dolores) was Pontecorvo unlucky.

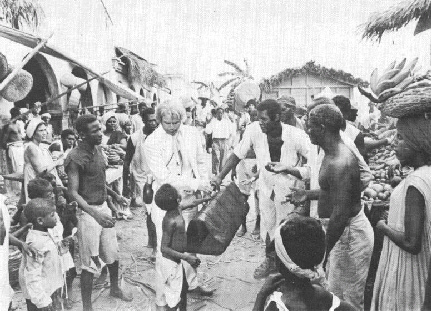

"...the native population scrounges for a living on the waterfront. It is here that Walker meets Jose Dolores, a porter who has learned that the only way to survive in a white man's world is to ingratiate yourself with foreigners." |

In Algiers, Brahim Haggiag, an illiterate peasant who knew nothing of movies, was metamorphosed into Ali La Pointe in every gesture and expression. Marquez was also an illiterate peasant who had never seen a movie when Pontecorvo met him. He was chosen without a screen test because his face so well suited Pontecorvo's conception of the character. But here the attempt failed. Pontecorvo found that Marquez could not turn or move on cue. A script girl had to tap his leg to remind him of his next movement. His part had to be played over and over in the evenings by Pontecorvo and Salvatori. Brando, out of the frame, would mime the facile gesture for Marquez who was on camera, while Pontecorvo shot over Brando's shoulder. Although Pontecorvo argues that after ten days Marquez improved dramatically, the film is marred by the unevenness of his movements and the unsureness with which he speaks.

At one point during the shooting, when Dolores was being coached in a completely mechanical way, Brando quipped, "If you are successful with this scene, I know someone who will turn over in his grave-Stanislavsky." Unfortunately for Pontecorvo, Stanislavsky's rest was not disturbed. It is not even clear from his performance if Jose Dolores understands what the film represents as his ideas. In the course of Burn! Dolores must mature- from a man without consciousness of his condition, completely unaware of the nature of his enemy, to a seasoned leader who knows exactly "where he's going," even if he's not always sure of "how to get there." He is to emerge as a mass leader. But with Dolores, and sometimes with Walker, motives and feelings are too often presented in long shot. We do not in fact see what we are told is before us.

Despite these weaknesses, Burn! is a beautiful film. It shares many of the strengths of Algiers, but its historical scope is far wider than the bare theme of independence from an oppressor long condemned by history as obsolete. A remarkable feature of Burn! is its truly cinematic style. Pontecorvo interweaves his two great preoccupations, music (and sound in general) with the imagery created by a constantly moving camera. The result is not a tract against neo-colonialism, but a ballet in which the dancers perform in accordance with a scenario predestined by the exigencies of a historical determinism. During the course of Burn! the visual style is altered with the changing fortunes of Jose Dolores. Walker's arrival in the first sequence is on a "painted ship upon a painted ocean." Birds chatter peacefully overhead and the camera pans a lush, green island. His second arrival, when his mission is to exterminate Jose Dolores and the revolutionaries, is in fog and mist, "under a cloud." The terrain of the last scenes of the film contrasts sharply with the first. All color has been bleached out. The sky is not blue, but white. The birds fly up to the sky to escape the smoke. Vultures predominate as the screen is filled with bodies and there are only blackened, charred trees. Pontecorvo demands of his camera that it find visual equivalents for the emotions of his people.

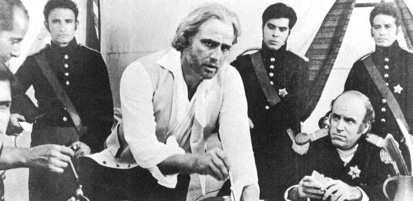

" 'Between one historical period and another,' says Sir William, readying himself for battle against Dolores and the rebels, 'ten years may be enough to reveal the contradictions of a century.' " |

But beyond cinematography, Pontecorvo uses sound, and frequently music, to convey the themes of his films. He admits to whistling projected musical themes on the set during shooting to govern his pacing, to determine how long to stay with a shot or on a face and when to cut away. Burn! begins with a gunshot heralding the titles which force their way onto a screen fragmented with stills from the film, one giving way to the next, in a violence accentuated by red background and music. The effect is of a film demanding that its message be seen and heard.

The central musical motif of the film, that associated with Jose Dolores, begins when the captain of Walker's ship points out to him an island in the harbor where the bones of slaves who died en route to Quemada are said to have been thrown. The music thus is interested not in Jose Dolores as an individual alone (he has yet to appear), but as a symbol of his suffering people. In the same way Walker, who shows Dolores' executioners how to tie the noose, ("See Paco," says the man, "this is how they do it.") personifies a vicious culture, a role that will supersede his impulse of affection and sympathy for Dolores.

Sound and image parallel each other as the thud of the plank lowered for the passengers to disembark is followed by a quick zoom back for a larger view of the wharves of Quemada. Creoles await the ship in eager anticipation, while the native population scrounges for a living on the waterfront. It is here that Walker meets Jose Dolores, a porter who has learned that the only way to survive in a white man's world is to ingratiate himself with foreigners: "Your bags, Senor," are his "smiling" first words. With a hand- held camera Pontecorvo takes us on a tour of the market place of Quemada, teeming with life, its bustle to be broken shortly by the arrival of a gang of black slaves in chains.

"Walker changed because there was nothing behind the side he helped... Men like Walker, full of vitality and action, then change the direction of this vitality. They go to sea, buy a boat, drink, beat people up. They don't believe in anything." |

Pontecorvo uses the zoom even more frequently here than he did in Algiers, and often for the same reason, as a means of conveying a rapidly changing state of consciousness in a character. There is a zoom to Brando's eyes as he looks through the bars of the windows at the funeral of the dead revolutionary, Santiago, who, had he lived, might have helped him in his plan to overthrow Portugal. The technique is also used with Jose Dolores as he lifts a stone against a Portuguese soldier mistreating a female slave. To emphasize the moment in which Walker sees Jose Dolores as a successor to the dead Santiago, Pontecorvo freezes the frame. With Pontecorvo the freeze frame is used as an equivalent to musical punctuation. Just as a musical theme can begin and then cease, only to start up again later, completing the motif, the freeze frame can punctuate the visuals. At this moment in the film the identity of Jose Dolores, and his future, have been sealed by his act of attempted rebellion.

Equally, Pontecorvo attempts to use editing as a means of thematic expression. He cuts from the bereaved wife of Santiago to a vulture against the sky, as she carries the body of her decapitated husband home. The vulture evokes the rapacity of those who exploit the people of Quemada and who murdered Santiago. Pontecorvo's editing style permits him a good deal of foreshortening, especially useful in a film with so complex a plot. Walker teaches Jose Dolores and his men how to use a weapon, concluding the lesson with the words, "the rifle is ready." The rapid cut, accompanied by percussion, is to a pan of the dead bodies of the Portuguese soldiers who have been killed as a result. Pontecorvo very frequently uses percussion, as in Algiers, as a means of heightening tension and emphasizing the crucial nature of an action.

For his close-ups Pontecorvo generally relies upon the eyes of his people. He chooses actors frequently on the basis of the intensity and expressiveness of this feature. The close-up of the eyes of Jose Dolores as he is about to attack Walker, who has just tested his metal by calling his mother a whore, immediately conveys his fury. Close-ups emphasize the tearful eyes of the children of Santiago helping their mother to remove the body. They become the tears of all those who have been made to suffer meaninglessly.

" 'Who will run your industries, handle your commerce, govern your island, cure the sick, teach in the schools?' Walker asks Jose Dolores, confident of his superior position.. -'Civilization is not a simple matter. You can't learn its secrets overnight.' " |

Such moments are contrasted with those in which Pontecorvo, using percussion, emphasizes the vitality and life force in the oppressed which emerges when they actively take part in wresting their freedom. After the killing of the Portuguese soldiers, Jose Dolores and the men and women who have helped him break into a dance. In his throat Jose Dolores echoes the shrill cry of the Algerian women when they urged their men to avenge the bombing of the Casbah. Reminding us of the earlier film, this scream from Dolores unites his struggle with that in Algeria. It also provides Pontecorvo with another opportunity to show that for people in underdeveloped countries faced with colonialism and later, neo-colonialism, the task is the same. The process of self-liberation follows a similar pattern. Jose Dolores dances with a baby in his arms, a frequent symbol with Pontecorvo, expressing his sense that the pain to be endured by Jose Dolores will be unmediated by success; it will be for future generations, who must continue his struggle, to achieve the final victory.

The defeat of the Portuguese in the film occurs all too quickly. It is rather inexplicable that a military (and naval) power like Portugal could be banished from Quemada with so little struggle or attempt at reinforcement. On the night of a carnival, the camera zooms in on the Portuguese governor about to be assassinated, ostensibly by Teddy Sanchez, but actually by Walker, whose role is epitomized as he holds the unsteady arm of his co-conspirator. Pushed out onto the balcony to face the people, Teddy Sanchez utters a whispered "freedom," displaying the timidity of his class faced with mass insurrection. A waving flag of Portugal appears mysteriously, providing the shot with rhythm and color- and Sanchez with the opportunity to tear it down. This action gives him his voice as well. As he now yells for "freedom!" the drums begin, expressing the restoration to life that liberation grants the people of Quemada.

The sympathy of the director for Jose Dolores is revealed most clearly in the music, resounding like a Gregorian Chant and sung by a black chorus, which accompanies Dolores and his army along the beach into the city. Because the music is so flamboyant, Pontecorvo begins with an extreme long shot of Dolores and his people, some walking, some on tired old horses, most in tatters, and all in absolute silence. Only when they are more nearly within our visual range do we hear the first notes of the organ which introduces the composition. The effect of this music is extremely powerful, if romantic. It succeeds, however, in rendering Jose Dolores a beatific figure, possessed in his devotion of more than human virtue. To reinforce this transcendent quality of his hero, Pontecorvo has a crowd of women and children from the town run along the beach greeting Dolores. The scene is done in silence with music alone, recorded, interestingly, by Pontecorvo in Morocco. It sets off the more grandiose music of the earlier moment. Smiling women with tears streaming down their cheeks reach out for Dolores, as if they were touching a god. Shots of arms, hands, parts of bodies, children, reinforce the motif of an enormous collective force converging like a wave in the struggle against exploitation. Pontecorvo also relies upon reaction shots to indicate the political point of view of the film. Jose Dolores' face changes effectively (and here Marquez seems quite adequate) when he learns that Sanchez has been made President of the Provisional Government. But the best reaction shot in the film occurs later, when a troop of British soldiers, complete with Red Coats, disembarks from the ship that has brought them to destroy the guerrillas. A baby-faced young soldier, marching proudly along, perhaps on his first assignment, smiles when he sees all the beautiful, richly dressed women who have come to offer welcome. His smile is slowly dissolved to an expression of extreme fear as he sees the cold fury in the eyes of the men of Quemada - also watching the scene on the wharf. The shot of the arrival of the British Army, marching through a crowd of waving handkerchiefs and cheers, parallels very closely the appearance of Mathieu and his paratroopers in Algiers. Both scenes establish that imperialism will use all the force and technology at its disposal to crush a rebellion aimed at removing its economic domination of impoverished lands. Because it reminds us so much of Algiers, the scene in Burn! serves again to reiterate Pontecorvo's view that the struggle of all these peoples is fundamentally the same. Their enemy always behaves in comparable ways because the objective of domination compels essentially similar stratagems and values.

Jose Dolores survives in power but a short time. The insuperable quality of the obstacles facing him is shown by the tracking camera moving through the chaotic palace rooms filled with debris, men sleeping on the floor, a howling dog, and general disorder. Dolores returns to the encampment of his people while the musical motif which has been associated with him is played, this time with pathos. The scene is a tableau vivant; the people reach out to him as they did on the beach. He smiles, but in his heart he knows that their freedom, for now, will be short-lived. The motif is again played with sadness when later, in a flashback, the rebel army is shown throwing down its guns.

Pontecorvo attempts to use music alone to convey the reason for Walker's return to Quemada. During a dissolute ten years, Walker had left the British Navy to inhabit slums. He no longer lives in keeping with the values and style of his class. The scenes which take place in England look as if they were filmed at the Cinecitta Studios outside of Rome. They are unrealistic to an extreme, puffed with atmosphere and fog, like Dickens seen through the eyes of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. The credibility of the entire sequence is saved only by the mobility of Brando's face when he is told by the emissaries of the Royal Sugar Company, now de facto ruler in Quemada, that he is needed. Walker scorns the offer until he is informed that it has something to do with "sugar cane." His face immediately changes as he remembers his days with Dolores. Accompanying his wistful and pained expression is the musical motif that we have associated with Jose Dolores and which represents all that is cherished in the film.

It is with this that Walker identifies and which possesses him. And it is here, in failing to develop the personal workings of his attachment, that the film appears arbitrary. Suddenly, in the next sequences Walker becomes a hardened mercenary who does whatever is necessary to preserve the holdings of a ruthless and self-serving sugar company, not caring what he must do as long as he "does it well."

We are presented a second time through the music with Walker's ambiguity. And again music alone cannot carry an entire psychology of character. On his return Walker sends a message asking Dolores to meet him for a discussion. Dolores' outraged emissary conveys the request (It will later be answered with the murder of three soldiers). But before this occurs, Walker, satisfied with himself and relishing the opportunity to meet his old friend once more, steps outside of his tent. He asks his sentry why he "isn't in the Sierra Madre with the others." (The name immediately suggests the " Sierra Maestra" of Cuba and encourages us to see in Jose Dolores a forerunner of Fidel Castro). The musical motif of Dolores once more envelops Walker as he walks out to look at the sunset. It is one of his moments of greatest happiness in the film. The music poignantly expresses the yearning in Walker, but it undercuts our belief in the mission Walker carries out so relentlessly, despite his feeling for Dolores. The element of self-awareness is missing and with it a means of integrating Walker's ambivalence within a coherent depiction of his psyche.

Pontecorvo uses no dialogue to condemn the soldiers, who must burn all of Quemada to capture Jose Dolores and his band of guerrillas. It is the music which judges them as they evacuate the villages. Sometimes sound and image overlap to increase the sense of irony. At one point, as people are being herded from their homes, we hear the words of the next scene: Teddy Sanchez tells a crowd of starving refugees, "You will know that it is not we who are responsible for this tragedy, but Jose Dolores."

A moment later a riot develops over the distribution of a cart-load of bread and, upon orders from General Prada, the people are fired on by the soldiers. A man of good intentions, the social democrat Teddy Sanchez, who believed all could live peacefully together under the rule of Royal Sugar as long as "adequate wages" were paid, is superseded by the more realistic General Prada who has known all along that Royal Sugar and a contented population were irreconcilables to be mediated only through the barrel of a gun. At one point during the evacuations, Pontecorvo tilts to a little boy with his hands up. The "nota ten uta" or sustained note, accompanying the image was written by Pontecorvo. He included it in the film, as he says, "superstitiously," since Burn! was the first of his films in which he did not collaborate on the music because only two months were available for the editing. Pontecorvo zooms in on the young soldier who captures Jose Dolores to explain the willingness of young men in Quemada to fight for Walker. One of Walker's soldiers declares he hopes Dolores remains uncaptured because as long as Jose Dolores lives, he has work and good pay. "Isn't it the same for you?" he asks Walker. The young boy who guards the captured Dolores stays with him and provides Pontecorvo with a means of allowing Jose Dolores to give his ideas expression through dialogue. He does not assail his captor; he tries to inspire and convert him. He tells the young man that he does not wish to be released because this would only indicate that it was convenient for his enemy. What serves his enemies is harmful to him. "Freedom is not something a man can give you," he tells the boy. Dolores is cheered by the soldier's questions because, ironically, in men like the soldier who helps to put him to death, but who is disturbed and perplexed by Dolores, he sees in germination the future revolutionaries of Quemada. To enter the path of consciousness is to follow it to rebellion.

General Prada is persuaded by Walker that Dolores induced to supplicate for freedom would serve their purposes better than the creation of a martyr, his spirit dangerously wandering the Antilles. Walker, his ambivalence surfacing, does not want the blood of Dolores on his hands. The scene in which Prada makes his offer to Dolores is especially well done. It occurs three-quarters off stage. We wait with Walker for the news, but all we hear are the muffled words "Africa" and "money," accompanied by a loud laugh from Dolores which chills us, as it must Walker. The episode is not shown because the film, in its admiration for Dolores, has rendered the plan absurd from the start. Nor is the defeated Walker shown at the end of the scene, although we hear his words, "I'm going to bed."

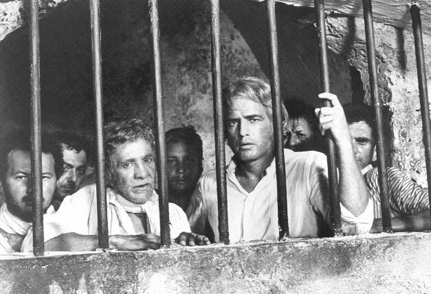

"Walker is personally undermined by this stark contrast between Dolores' satisfaction in moral conviction and his own emptiness, which he only now fully registers. The taste of victory is bitter." |

The last interview between Walker and Dolores is powerful. Walker desperately wishes to set Dolores free. Dolores refuses to speak to him. The camera focuses on the face of Brando who, having been superseded in his superiority and moral strength by Dolores as a mature revolutionary, cannot understand why a man would give up his life if he has a chance to escape. Dolores has purpose and meaning in his life. Walker by this time has none and only now is confronted, looking at the transformed Dolores, by what Pontecorvo has called "his own emptiness." Pontecorvo has described the shooting of this scene with great poignancy: " Walker is desperate when Dolores refuses. He sees his own emptiness before his eyes. And we stopped one day for this scene because Brando was afraid. It may appear very strange, but Brando, because of his sensibility, after years and years of sets, after years and years of success, is very often afraid of difficult scenes, extremely afraid. And he is tense and nervous when he is in such a situation. In this situation he was not able to function. The dialogue was originally longer... we cut out all the dialogue and I told someone to buy Cantata 156 of Bach because I knew that it gives the exact movement of this scene. And I cut all the dialogue. Without saying anything to Brando, I said, we will shoot now, we have waited too long, we will try to shoot. I put the music on at the moment when I wanted him to open his arms and express his sense of emptiness. I put on the music without telling him. I said only, "Don't say the last part of the dialogue." He agreed. He was happy to do this; he said it was stupid to use too much dialogue. From this moment he was so moved by the music that he did the scene in a marvellous way. When he finished the scene, the whole crew applauded. It was more effective there than on the screen later. The sudden tension we obtained was surprising. And Brando said this was the first time he had seen two pages of dialogue replaced by music."

Pontecorvo zooms to Walker as he listens to Dolores' final message which breaks his silence: "Ingles, remember what you said. Civilization belongs to whites. But what civilization? Until when?" The stabbing of Walker on his way to the ship by an angry rebel comes simultaneously with a repetition of the Algerian cry for freedom. It is followed, accompanied by percussion, by a pan of inscrutable, angry black faces on the dock. The frame freezes, fixing their expressions indelibly in our minds. The music of the end is a religious choral piece. Played over the final moments of life remaining to Walker who lies in the dust, it becomes at once an apotheosis, very moving and romantic, as it heralds in victory the fall of the tormentor. The feeling left with the audience is simultaneously one of horror and vindication, although the actual murder of Walker occurs long after his moral demise.

Far more than Algiers, with its virtual equation of the vast violence committed by the French with that of the Algerians, Burn! was a courageous film for Pontecorvo to make. There are few films as passionate or as uncompromising about the real workings and nature of imperialism as a world order, nor a film which identifies so feelingly with the victims of neo-colonial rule. Not since Eisenstein has a film so explicitly and with such artistry sounded a paen to the glory and moral necessity of revolution. Even had United Artists not attempted to sabotage Burn!, it would be a film deserving wider viewing and critical attention.

Review- Copyright Cinema Magazine |